Jenna Stoeber recently published a video review of the new Nintendo Museum which opened in Kyoto, Japan on October 2nd 2024. It was – and still is – an immediate hit, with fans of the beloved video game company flocking from around the world to visit. But the museum itself seems to leave much to be desired – as Stoeber mentions in her review, many of the museum’s displays are frustratingly devoid of placards, leading her to refer to the museum as more of a ‘material archive’ that puts the company’s products first before any actual context or insight. This is a criticism that is echoed in other reviews of the museum as well (MacDonald 2024, Kidman 2025).

But why? Isn’t the point of a museum to learn about things, to see different perspectives and come away with some new insight or knowledge? In a perfect world, perhaps – but of course, museums have historically been a means of telling a particular story, often in service a specific narrative driven by societal, political, or in the case of a company, even financial needs. As Stoeber notes in her video review, the Nintendo Museum is very focused on telling the story of its history as a games company, with no mention of its previous investment ventures in other industries (taxis, hotels, etc.). MacDonald’s review also echoes this sentiment, noting that visitors are “seeing exactly the version of Nintendo’s history the company wants you to see”. And for Nintendo, this include what is already known and assumed about its products – you, as a member of the general public, know that the Switch is a portable gaming console that can be purchased from Nintendo, so what else is there to it? So long as the public knows that their product exists, that’s already achieving what a company like Nintendo sets out to do – a ‘museum’ like this simply reiterates that, no additional information necessary.

Stoeber’s framing of the Nintendo Museum as a ‘material archive’ rather than a museum made me immediately think of another recently opened institution – the V&A East Storehouse in London. Presented as an innovative approach to transparency in museum collections (as well as an architectural marvel), the Storehouse presents much of its storage to the public – albeit mostly without labels (in some cases, there are QR codes to allow visitors to connect with the digital collection records). It is an intentionally overwhelming experience, in which visitors are dazzled by the spectacle of thousands of objects but without much acknowledgement as to what they actually are, or any context connected to them. As Dan Hicks (2025) writes in his review, this presentation begs the questions: “what are we not being shown? Not what’s hidden exactly, but what is being strategically distracted from…?” Hicks makes the point that this new space comes within the context of multiple scandals in the sector that demonstrate the failures of major museums to account for their own collections; similarly, the broader decolonisation movement has pushed questions of ownership and transparency within museums into public debate. The V&A East Storehouse is simply performing the very transparency it boasts about.

While two instances don’t necessarily make a trend, I do think that we can connect these highly publicised venues with an intentionally ‘contextless’ (or ‘context light’) approach to collections to another passing fad – the ‘selfie museum’. This is something I’ve written about in the past and refers to a sort of pop-up exhibition (often touted as a ‘museum’ of sorts) that basically acts as an immersive art installation with the primary focus of having visitors take photos of themselves in the space. In my initial blog post about this phenomenon, I was quite positive about the potential for a much more participant-oriented approach to museum experiences and visitor engagement.

But what I missed in my initial writing – and perhaps this is something that has only become more apparent since then – is the commercial aspect to these spaces. As Pardes (2017) notes in regards to the Museum of Ice Cream, the New York iteration of the exhibition had thirty corporate sponsors attached to it, with several rooms of the museum explicitly themed around its corresponding sponsor (for example, a Tinder-sponsored room encouraged visitors to use an app to find their “true flavour match”). None of these so-called ‘museums’ have placards, because they aren’t there to convey knowledge – they are there to present ‘experiences’ first and foremost, and more often than not, those experiences are entwined with corporate interests and financial gain. In her critical essay on these pop-up experiences, Amanda Hess (2018) writes that within these spaces, “the idea of ‘interacting’ with the world is made so sickly transactional that our role is hugely diminished”. And I think that really hits the nail on the head – the visitor is primarily viewed as a customer, who has paid an admission fee to experience something. And through sponsorship and branding, that experience is heavily curated – and part of that includes the decision to forego any form of context provided beyond what can be seen.

So should we be worried about these ‘contextless museums’ become more of the norm? While I don’t think the traditional museum, with its placards in full view of the visitor, is ever truly in danger of going away, I do think that we may see more of these material archives or art experiences appear, particularly as representative of institutions and corporations with longstanding histories of being in the public eye. Because what is the purpose of additional context if there is an underlying assumption that you, as a visitor, already know what you’re getting into? Nintendo understands its current audience are fans of their video games, so why should they feel compelled to add their historic context to their museum? Their visitors will be there to play the games they already know and enjoy, and see artefacts relating to the products they have likely already purchased in the past.

Perhaps the real issue then is the encroaching of corporations into the museum space – something that has already caused fierce debate and protests when it comes to the use of sponsorship for whitewashing complicity in climate change and other forms of violence (Procter 2022, Chow 2025). If museum spaces are at risk of being co-opted more fully by corporations and other financial investments, what will be sacrificed for a more transactional experience? If corporations find that written context and interpretations run the risk of fracturing their public image, will the push towards contextless exhibitions become more prevalent? And if a sector with so many financial woes sees a new means of cutting costs – by removing the human labour required to add the context to exhibits – would it agree with such a massive change to museological practice? I’d love to say the answer is a resounding ‘no’, but as we continue to see more and more museums facing closure due to financial reasons, I worry that the enticing call of corporate money may become harder to deny than ever before…

References

Chow, V. (2025) Why Corporate Sponsorship Is Getting Riskier for Museums. ArtNet. Retrieved from https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museums-corporate-sponsors-2690432

Hess, A. (2018) The Existential Void of the Pop-Up ‘Experience’. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/arts/color-factory-museum-of-ice-cream-rose-mansion-29rooms-candytopia.html

Hicks, D. (2025) What isn’t at the V&A Storehouse. ArtReview. Retrieved from https://artreview.com/what-isnt-at-the-va-storehouse-opinion-dan-hicks/

Kidman, A. (2025) Nintendo Museum Kyoto Review: Great Content, Lacking in Context. Alex Reviews Tech. Retrieved from https://alexreviewstech.com/nintendo-museum-kyoto-review-great-content-lacking-in-context/

MacDonald, K. (2024) Pushing Buttons: At Nintendo’s new museum in Japan, I found a nostalgia-laced trip down memory lane – not a history lesson. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/games/2024/sep/25/pushing-buttons-nintendo-museum-kyoto

Pardes, A. (2017) Selfie Factories: The Rise of the Made-for-Instagram Museum. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/selfie-factories-instagram-museum/

Procter, A. (2022) The Backlash Against Oil Sponsorship Can Push for Broader Change in Museums. Hyperallergic. Retrieved from https://hyperallergic.com/717649/backlash-against-oil-sponsorship-can-push-for-broader-change-in-museums/

Stoeber, J. (2025) Nintendo’s Museum Problem. YouTube Video, retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0N6qnOihHg

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

Please also consider donating to fundraisers for Palestinians currently in Gaza by clicking here.

One response to “Is the Museum of the Future Contextless?”

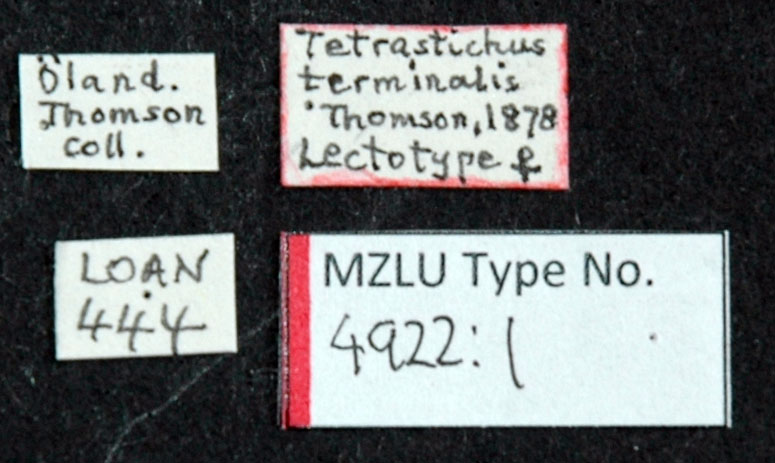

[…] Animal Archaeology A photo of four paper museum labels reading (clockwise from top left): Oland. Thomson. Coll., Tetrastictus terminalis Thomson 1878 Lectotype, MZLU Type No 4922, and Loan 444 (Photo Credit: Biological Museum, Lund University) Jenna Stoeber recently published a video review of the new Nintendo Museum which opened in Kyoto, Japan on October 2nd 2024. It… […]

LikeLike