This past Christmas, my dad gifted us an Atari 2600 from about 1982. Originally launched as the Video Computer System (VCS) in 1977, this compact console would eventually be renamed as the Atari 2600 in 1982, coinciding with the launch of the company’s new 5200 SuperSystem console (Lendino 2022). While we have no idea if we’ll be able to get this to work (luckily, my partner is a collector of ‘retro tech’ so will be tinkering with this for the foreseeable future), what I was really excited about was the paperwork that was included in the box.

You see, I’ve always loved game manuals. Back in the day, they used to be really in-depth and sometimes even lore-friendly, so I absolutely loved pouring through the manual of a newly purchased game while waiting for the game to install. So it really delighted me to see that whoever my dad purchased this Atari 2600 from had not only included two bags of game cartridges, but also their corresponding game manuals as well.

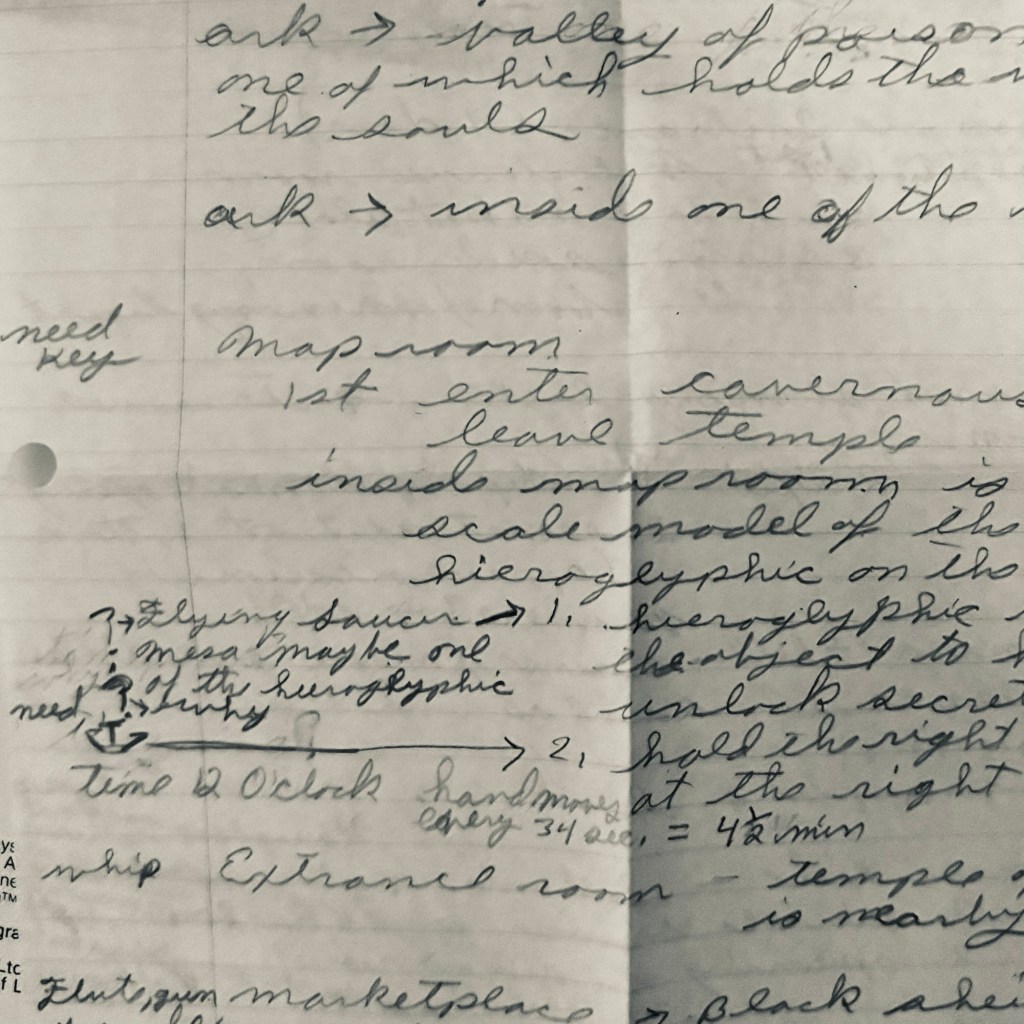

But that wasn’t all…while leafing through the Raiders of the Lost Ark manual, I found what seemed like an old piece of folded up paper. Upon further inspection, we realised that this was a series of handwritten notes detailing a ‘walkthrough’ of the game, revealing how to beat certain levels through the use of certain objects and strategies. It’s such an incredible artefact in its own right – a look at what gaming was like pre-Internet, when you couldn’t just look up a walkthrough guide or video.

Finding hidden video game gems seems to be in the air this past week – around the same time the Atari 2600 got sent to me, the Video Game History Foundation launched early access to their new digital archive. It’s an amazing collection of materials relating to video game history, including publications, memorabilia, and even game development materials (Salvador 2025). Representing years of work curation, digitisation, and collaboration with video game professionals and enthusiasts alike, I think what makes me most excited about this new archive is how much cultural context it provides to not only how video games were created, but also how they were played and received at the time – something that I worry is often missing in conversations of video game preservation (after all, you can emulate, remaster, or re-release older games, but how can you preserve what it felt like to play a Lucas Arts point-and-click game without access to the Internet to find a solution to a puzzle?).

But the other thing that got me excited was seeing the VGHF’s recent post on BlueSky, asking for folks visiting the archive to share what they have been finding, as they “don’t even know 100% of what’s in here”! And I just really loved seeing such encouragement of curiosity within archival spaces and it really got me thinking of why I have truly loved working within digitisation and crowdsourcing in archives over the last few years.

Since 2022, I’ve been working in digital crowdsourcing for museums and archives, producing two projects based on photographic collections held in Bradford (How Did We Get Here? and Bradford’s Industrial Heritage in Photographs). It’s been an incredible honour to not only bring local collections to a much larger audience through platforms like Zooniverse, but also see how so many people from around the world engage with histories of industry, immigration, colonialism, and racism, often on very emotional and personal levels. It’s also fascinating to see what people derive from the archives themselves – sometimes it triggers a personal memory, or perhaps it reflects something so different to their own life experiences that they’re able to view things from a new perspective. Doing this work made me wish that more people had access to archives, whether in-person or online, as its not just a valuable experience for participants, but also for those of us managing or working in the archives as well! Despite working so closely with these materials, I was still learning new things from the digital volunteers. It’s a shame that my time with these projects were ultimately so brief (as postdoctoral projects often are!) – but I’m really thankful for the time I have been given to do this sort of work (and hope I can do more in the future!).

Engaging with any archival document or object is a completely personal and often individualised thing, where two people may get completely different experiences from the same object. Our understanding of an object, our sensory experiences, the meanings and values we ultimately derive from these objects – these are all deeply personal things that are only drawn out through engaging with the archive (Lester 2018, p. 83). We gain so much by opening up access to archives – not just in collective appreciation of the objects inside, but also in gaining new perspectives on the materials too.

I’m thinking about those handwritten notes from a gamer, potentially from 40 years ago. The paper feels so fragile in my hands, the smell is so dusty and old – and yet, it also instantly reminds me of when I was a kid trying to play Myst for the first time, with a notebook in hand to scribble down notes as I tried and failed to get far in the game. Such a delightful and meaningful surprise hidden inside this Atari 2600 box…and I wonder how many similarly delightful and meaningful surprises lie inside the VGHF archive as well.

You can support the Video Game History Foundation by donating here.

References

Lendino, J. (2022) The Atari 2600 at 45: The Console That Brought Arcade Games Home. PC Magazine. https://uk.pcmag.com/games/142576/the-atari-2600-at-45-the-console-that-brought-arcade-games-home

Lester, P. (2018) Of Mind and Matter: the Archive as Object. Archives and

Records, 39(1), pp. 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/23257962.2017.1407748

Salvador, P. (2025) The VGHF Library Opens in Early Access. Video Game History Foundation. https://gamehistory.org/vghf-library-launch/

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

Please also consider donating to fundraisers for Palestinians currently in Gaza by clicking here.

One response to “Archives are for the Gamers (and Everyone Else): Making Archives Available for All”

[…] Animal Archaeology A slightly weathered red box, showcasing the Atari logo and the numbers 2600 in big white font. Underneath that in black text are the words, „The World’s Most Popular Video Game System!“ This past Christmas, my dad gifted us an Atari 2600 from about 1982. Originally launched as the Video Computer System (VCS) in 1977,… […]

LikeLike