Please note that this blog post contains spoilers for the game “Heaven’s Vault”.

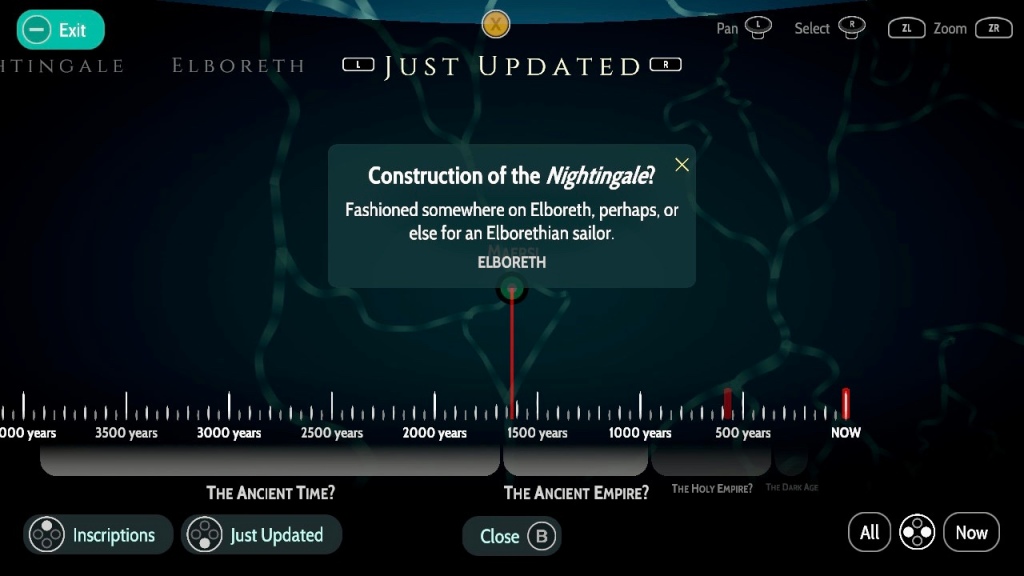

As I wrote in a post almost a year (!!!) ago, I finished my second playthrough of Heaven’s Vault (Inkle Studios, 2021). And perhaps one of the things that struck me most on this replay was just how long the travel sequences were – for those who have not played, the main method of travel in the universe of Heaven’s Vault is by “sailing” space rivers which consist of flows of oxygen, hydrogen, and ice. These sailing sequences aren’t particularly action-heavy, with the only input of the Player consisting of steering the ship to the correct fork and hitting a button to check out ruins that are along the rivers.

However, they are long…like, really long. The map for the game is deceptively large, with many twisting rivers that coincide with other pathways, making it easy to get lost as you unlock more areas and expand your exploration range further. And honesty? It gets a bit…annoying. And boring. To give the game developers credit, there is an “auto-travel” option where you can hand off steering duties to your robotic companion, basically teleporting you to your destination. But there’s a catch – your robotic companion is unable to stop at any unexpected ruins you might come across, meaning that you can easily miss out on exciting finds that may give further clues towards the central mystery of the game.

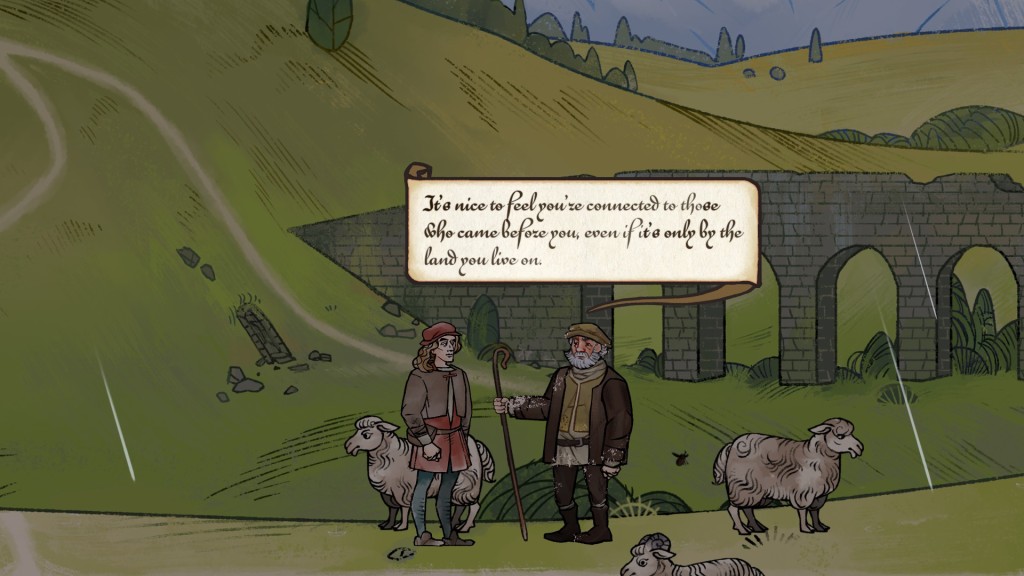

Obviously, Heaven’s Vault is a video game about archaeology so there are some very explicit similarities between its core gameplay mechanics and archaeological methods. But I think we can also, perhaps more abstractly, relate the long and winding travels on Heaven’s Vault’s space rivers to the often long, and sometimes winding process of archaeology, a discipline in which research is constantly revisited and revised over long periods of time, with unpublished data from decades earlier finally getting worked into more recent, published work, and old, outdated theories re-invented over time. And yet we also see an impatient side to archaeology as well – the short turnarounds expected from most fieldwork, the need to produce results as soon as possible due to contractor needs and funding policies.

Thinking about patience (or the lack thereof on my part) in Heaven’s Vault reminds me of “slow archaeology”, which was a concept first put forth by archaeologist William Caraher. In his original 2013 article, Caraher suggests the use of a slower archaeology in contrast to the time-efficient, assembly line-like approach to fieldwork that has been facilitated by digital tools and other technical innovations that are mainly accessible to larger, more well-funded projects. A slower archaeology, on the other hand, is often embodied by smaller, less-funded projects with small teams working multiple roles on-site. This, in Caraher’s view, returns archaeology to a state of craftwork, where manual handling of the work requires more attention at a slower pace, maintaining an embodied experience and knowledge that isn’t disrupted through technological processes.

In response to Shawn Graham’s (2017) critical view of slow archaeology as one that also requires a level of privilege not afforded to underrepresented and otherwise marginalised archaeologists, Caraher (2019) has more recently suggested a reframing of slow archaeology to be more about an “archaeology of care”; that is, an archaeology that takes care to understand how the discipline is ultimately shaped and informed by the relations between individuals, tools, methods, and technologies. Regardless of whether or not archaeology is more craft or industry, maintaining this critical eye throughout keeps archaeology embodied as a method of knowledge-making and cautions us to not get too complacent with the increasingly digitised workflows of the discipline.

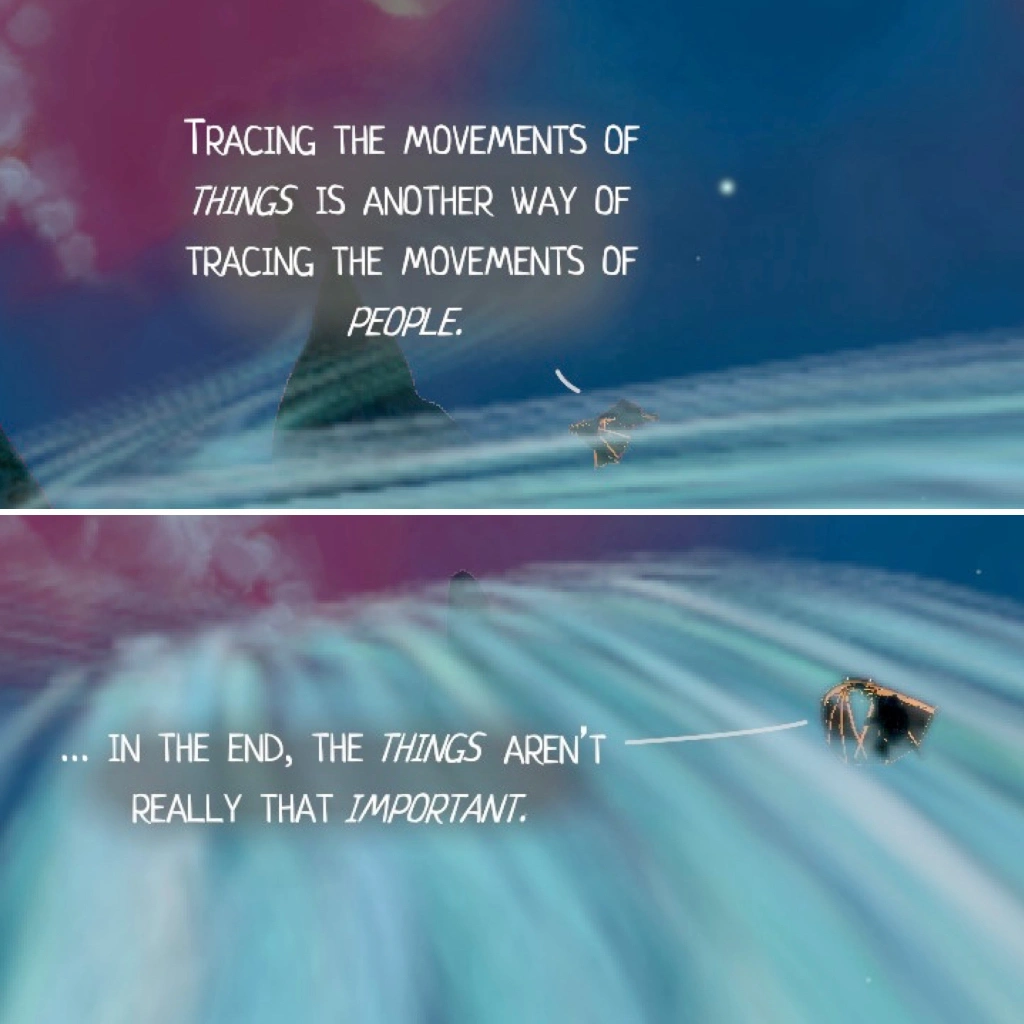

Reflecting back at my impatience at the travel system in Heaven’s Vault and my penchant for using the auto-travel button, I can see how that runs counter with the idea of “slow archaeology” – in automating this travel (in the most literal way possible given that a robot takes over for you), you are missing out on embodying that experience, even if its long and boring. And without that embodiment, you miss out on being able to make off-the-cuff decisions or discoveries, such as stopping at a random ruin which gets bypassed in automation. In bypassing this experience, I can still get to a conclusion – ignoring manual sailing doesn’t impact the ending of the game, for example. But I do miss out on smaller elements that could have become something much greater through my experience with it, producing a result that maybe isn’t deemed to be productively important in the grand scheme of things, but ultimately enhances my understanding by interacting and engaging with it.

Something that I think we can all do to remember that is emphasised by Heaven’s Vault’s story is that archaeology is an “incomplete” story, that none of us will really see the completion of our understanding of the past as we ourselves are drawn into histories through the passage of time. This isn’t to say that project and fieldwork results aren’t useful, of course! But it may be that they’re not the true goal of a slower, more caring archaeology – that we don’t have to streamline and make things more efficient and productive, but strive towards being “in the moment” with the past that we handle, engaging archaeology in order to enable a more thoughtful and embodied approach to our understanding.

You can buy Heaven’s Vault now for the Nintendo Switch, Playstation, and for PC via Steam.

References

Caraher, W. (2013). Slow archaeology. North Dakota Quarterly, 80(2), 43-52.

Caraher, W. (2019). Slow archaeology, punk archaeology, and the ‘archaeology of care’. European journal of archaeology, 22(3), 372-385.

Graham, S. (2017). Slow Archaeology? Electric Archaeologist. Retrieved from https://electricarchaeology.ca/2017/03/20/slow-archaeology/

Inkle Studios. (2021). Heaven’s Vault, video game, Nintendo Switch. Cambridge: Inkle.

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can find my PayPal here.

Geralt, the main character, is a Witcher (have I written that word enough yet?). This means he’s been trained and physically & genetically enhanced in order to combat monsters and other deadly creatures.

Geralt, the main character, is a Witcher (have I written that word enough yet?). This means he’s been trained and physically & genetically enhanced in order to combat monsters and other deadly creatures.