This is the transcript from a talk I gave in April 2022 for the Enabled Archaeology session of the CIfA2022 Conference. It is an extension of my original blog post on Digging While Depressed, which you can read here.

Digging While Depressed (Fitzpatrick 2018, 2019) was the result of my experiences after being injured on-site during the 2018 fieldwork season, which had led to me spending the next several weeks off-site and alone, tending to my injured arm (and pride) while the rest of the excavation team were on-site. I was filled with many emotions, all of them negative – I felt embarrassed at my ineptitude, guilty that I had let my PhD supervisors down, and ashamed that I could not face my newfound fears that the traumatic event instilled in me. Perhaps the strongest emotion I felt during this period was loneliness as well – not only being away from my colleagues for most of the day as they excavated, but also from friends and loved ones during the fieldwork season. Unsurprisingly, these emotions led me into a major depressive episode, and so I took to Twitter to express these feelings while using the hashtag #DiggingWhileDepressed. To my surprise, other archaeologists from around the world shared their own stories and experiences, indicating that this was a much larger issue than I may have previously imagined. Through these brief discussions on Twitter, as well as some follow-up discussions via email and in-person, several shared factors where identified among these stories. For example, fieldwork is inherently isolating and creates periods of inconsistency in an archaeologist’s daily routine. Employment is similarly inconsistent, with casualisation rampant in commercial sectors across several countries; this creates a sense of precarity, particularly around income, which can cause anxiety. Fieldwork is labour-intensive, often working in poor climates and with similarly poor off-site accommodations. This all culminates in a general notion that discussing mental health among colleagues is “taboo,” that archaeologists should just “get over it,” and that suffering “validates” the work they are doing. I ended my original paper with a call for more concrete actions and practices in place to support the emotional and mental well-being of archaeologists as part of a broader initiative for making the field more accessible for those with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and neurodivergence in the field.

Although the hashtag itself never become particularly popular or really survived beyond 2018, the discussion it generated seems to have continued since then. For example, there seems to be more standardised practices in place to support mental health in the field (e.g., Davis et al. 2021), and calls for treating accommodations and accessibility as part of embedded a more ethical practice into archaeological work (e.g., Peixotto et al. 2021). There has also been work exploring other elements adjacent to the original discussion, including research into how isolation from social media factors into mental health (Eifling 2021) and the pressure to “pass” as non-disabled in the field when you have an invisible disability (Heath-Stout 2022). In my own work, I have continued to explore the ways in which archaeology as it is currently practiced encourages ableist attitudes, and how these elements are further connected to problematic parts of the field, such as its entrenched notions of toxic masculinity, racism, and colonialism (Fitzpatrick 2020). Ultimately, this has led me to conclude that there is still much work to be done with regards to expanding inclusivity in the field, which has only been further emphasised by the events of the last three years.

Much has drastically changed since I originally wrote about Digging While Depressed, both globally as well as personally. In early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic saw major national lockdowns across the world, with restrictions lifted and placed intermittently due to fluctuations in hospitalisations and the rise of new variants. At the same time, the Black Lives Matter movement has seen a revival which has spread from the United States to across the globe, causing a flurry of public discussion on equality, diversity, and inclusion, and spurring the creation of many EDI initiatives across sectors and organisations, including some that tackle issues of accessibility and disability due to the interventions of Black disabled activists and other disabled people of colour. Through 2020 and 2021, many accommodations for flexible working and socialising were made during periods of lockdown, which not only highlighted the general lack of accessibility of many workplaces and events pre-pandemic, but also allowed for many disabled people to finally participate in these previously inaccessible environments (Beery 2020). However, despite cases continuing to happen in the thousands around the world, many countries have initiated a “return to normalcy,” dropping nearly all restrictions and health requirements. As such, many disabled people once again feel as though they are being excluded from everyday life (Barbarin and Dawson 2021).

As for me, I have continued to be treated for depression through medication and occasional bouts of therapy. This lead to a breakthrough in 2021 that my anxiety disorder was ultimately the underlying factor behind most of my depressive episodes, which led to my treatment being adjusted. However, I began to see a decline in my physical health at the same time (Fitzpatrick 2022); this included worsening mobility issues which has resulted in more frequent use of mobility aids (e.g., canes, limb braces), the inability to do physically demanding activities, and the recent realisation that my chronic pain was actually abnormal. I am currently in the process of getting a diagnosis from various specialists, with joint hypermobility syndrome and anaemia recently identified. As such, I have been recognising that my ability to “do” archaeology (as it is widely understood) is constantly diminishing and has exacerbated my anxiety as I enter an already-dwindling job market after graduating during a pandemic.

Looking at the last three years in both a global and personal context, there are several recurring themes that we can extrapolate into a discussion on ableism and enabling archaeology for everyone. To start, the almost immediate shift in practice across many workplaces to focus on flexible working and homeworking indicates that change is possible. Unfortunately, we have also seen how quickly these accommodations can be taken away, and how disabled people are still considered an afterthought throughout this planning. At the same time, there has also been an increased awareness for the need for further inclusivity and diversity across sectors, no doubt due in part to the Black Lives Matter movement instigating public discourse on existing inequalities, particularly for Black disabled people and other disabled people of colour. From a personal perspective, I am quickly learning just how inaccessible archaeology is, which has also been further emphasised by the removal of pandemic accommodations for many sites and workplaces. In addition, I have realised just how easy it is to become disabled in the context of how society views disability, and how quickly it has changed my perspective of what I can and cannot do in archaeology, which in turn limits my ability of doing archaeology in the ways in which it is widely practiced today.

With the context from the last few years in mind, we can return to highlighting this major issue of ableism in archaeology, one of the many remnants of the colonialist toxic masculinity that was foundational to the development of the field and its public perception. Ableism is perpetuated through a continued lack of accessibility, which lends to poor environments and workplaces that exacerbate poor mental health and well-being – and not only just for disabled archaeologists, either.

A lack of inaccessibility can lead to feelings of isolation and “Imposter Syndrome,” which can worsen poor mental health and lead to people ultimately leaving the field. But by creating inclusive and accessible spaces, we can make the field more welcoming to everyone – and we should be moving beyond the notion that archaeological fieldwork must be about hard labour, physical risk, and danger, as this perpetuates the notions of a toxic masculinity which is emboldened and measured in strength by its ableism.

That said, we should still be centring disabled archaeologists in discussions of accommodations and accessibility; in addition, it should be noted that not everyone who has poor mental health or mental health conditions identifies as disabled, that many disabled people do not have mental health conditions, and that there are many people (such as myself) who consider themselves to be multi-disabled with mental health conditions and other forms if disability. Although our individual experiences and conditions will vary, ultimately we are all impacted by the perpetuation of ableism in the field. And although I have used the word “accommodating” and “accommodations” in this paper, I want to stress that, in actuality, we need to be moving beyond “just” accommodating – instead, we should be striving towards removing the remnants of entrenched ableism in archaeological practice and theory, expanding our conceptions of what entails fieldwork and research, and reconceptualising our assumptions of what “doing archaeology” actually means.

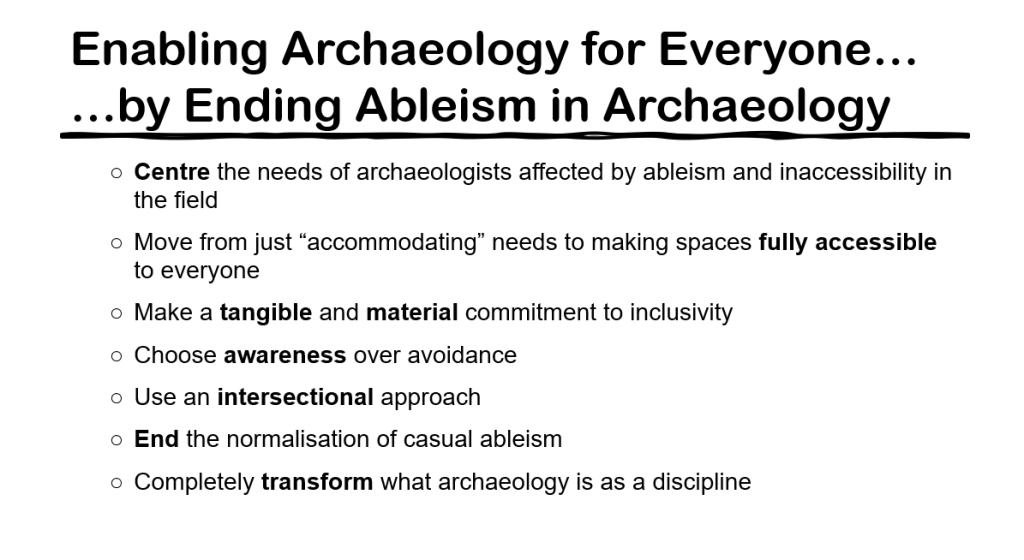

To end this paper, I would like to propose several ways to move towards a more enabling form of archaeology for everyone, with a focus on eradicating ableism in the field. To start, I want to reiterate that we must centre the needs and experiences of archaeologists affected by ableism and inaccessibility in the field. We must move the goalposts from “just” accommodating needs and actually move towards making spaces fully accessible to everyone. And although I know that accessibility can require a substantial amount of resources, at this point there is no excuse for it to not be part of any early planning or considerations for a project or organisation – if you are committing to diversity and inclusion, that means you must be tangibly and materially committing. I also want to return to a concept I introduced in my original paper (Fitzpatrick 2019): awareness over avoidance. In other words, we should be normalising discussion of disability and mental health, which can be supported through the creation of more inclusive spaces where discussions can occur freely and without the fear of retaliation. We must also be taking an intersectional approach to accessibility as well, as the needs of BlPOC and/or LGBTQ+ disabled archaeologists may differ from white and/or cis-heterosexual disabled archaeologists. In addition, there are also issues specific to these marginalised groups that will exacerbate poor mental health, such as racism, homophobia, transphobia, and queerphobia. Finally, we need to commit to ending the normalisation of casual ableism in the field – this includes ending the celebration of suffering during fieldwork as some sort of “rite of passage,” and of pushing excavation as the only means of doing “real” archaeology. Archaeology as a field must transform and progress to meet the needs of everyone – otherwise we will continue to lack in diversity, and archaeology will truly suffer for it.

References

Barbarin, I. and Dawson, K. (2021). “Normal” Never Worked for Disabled People – Why Would We Want to Return to It? Refinery 29. URL https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/workplaces-need-change-for-disabled-people

Beery, Z. (2020). When the World Shut Down, They Saw it Open. The New York Times. URL https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/24/style/disability-accessibility-coronavirus.html

Davis, K. E., Meehan, P., Klehm, C., Kurnick, S., & Cameron, C. (2021). Recommendations for Safety Education and Training for Graduate Students Directing Field Projects. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 9(1), 74-80.

Eifling, K. P. (2021). Mental Health and the Field Research Team. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 9(1), 10-22.

Fitzpatrick, A. (2018). Digging While Depressed: Struggling with Fieldwork and Mental Health. Animal Archaeology. URL https://animalarchaeology.com/2018/07/09/digging-while-depressed-struggling-with-fieldwork-and-mental-health/.

Fitzpatrick, A. (2019). #DiggingWhileDepressed: A Call for Mental Health Awareness in Archaeology. Presented at the Public Archaeology Twitter Conference.

Fitzpatrick, A. (2020). You will never be Indiana Jones. Lady Science. URL https://www.ladyscience.com/essays/you-willnever-be-indiana-jones-toxic-masculinity-archaeology

Fitzpatrick, A. (2022). On Flare Ups in the Trenches: Personal Reflections on Disability in Archaeology. Animal Archaeology. URL https://animalarchaeology.com/2022/01/06/on-flare-ups-in-the-trenches-personal-reflections-on-disability-in-archaeology/

Heath-Stout, L. E. (2022). The Invisibly Disabled Archaeologist. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 1-16.

Peixotto, B., Klehm, C., & Eifling, K. P. (2021). Rethinking Research Sites as Wilderness Activity Sites: Reframing Health, Safety, and Wellness in Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 9(1), 1-9.

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can find my PayPal here.