-

Bones and All: A (Pre)History of Death & Display in “28 Years Later”

Please note that this blog post has some slight spoilers for Danny Boyle’s 2025 film 28 Years Later. Read ahead at your own risk! In the final act of 28 Years Later, the audience is introduced to Ralph Fiennes’ character Dr Ian Kelson, a former GP who is thought to have lost his mind in…

-

The (Entirely Inaccurate, Completely Nonsensical) Plastic Skeleton Wars Continue

Let’s be real – you know exactly what this blog post is about. I’ve been writing about these cursed plastic objects for years now. After doing an overview of the worst iterations of animal skeleton decorations in 2017, an investigation as to why they look as horribly and inaccurately as they do in 2021, and…

-

Is the Museum of the Future Contextless?

Jenna Stoeber recently published a video review of the new Nintendo Museum which opened in Kyoto, Japan on October 2nd 2024. It was – and still is – an immediate hit, with fans of the beloved video game company flocking from around the world to visit. But the museum itself seems to leave much to…

-

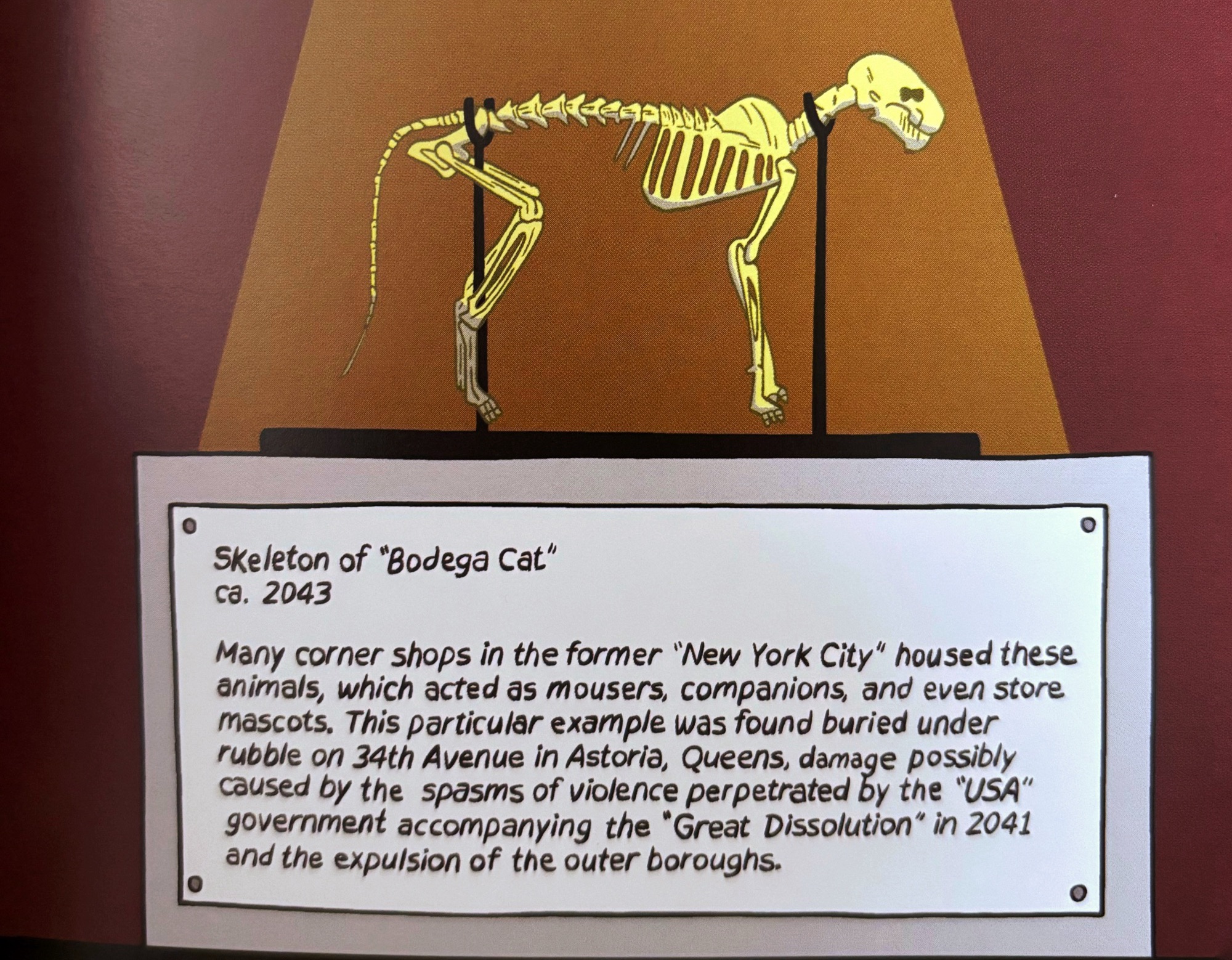

Mattie Lubchansky’s ‘Simplicity’ and Weaponising the Museum of the Future

The following blog post will contain spoilers for Mattie Lubchansky’s recent book Simplicity, which is out now and I highly recommend folks – especially those of you who work in the museum and anthropology fields – read it first! Simplicity (Lubchanksy, 2025) is not about museums. I mean, it kinda is – but it’s more…

-

Who Gets to Feel Good in Archaeology?

Over the past decade, there has been a lot of attention drawn to the benefits of archaeological fieldwork on the mental health of participants (e.g., Finnegan 2016, Rathouse 2019, Everill et al. 2020, Dobat et al. 2022). And while it is wonderful to see people have such a positive experience with archaeology, I have to…

-

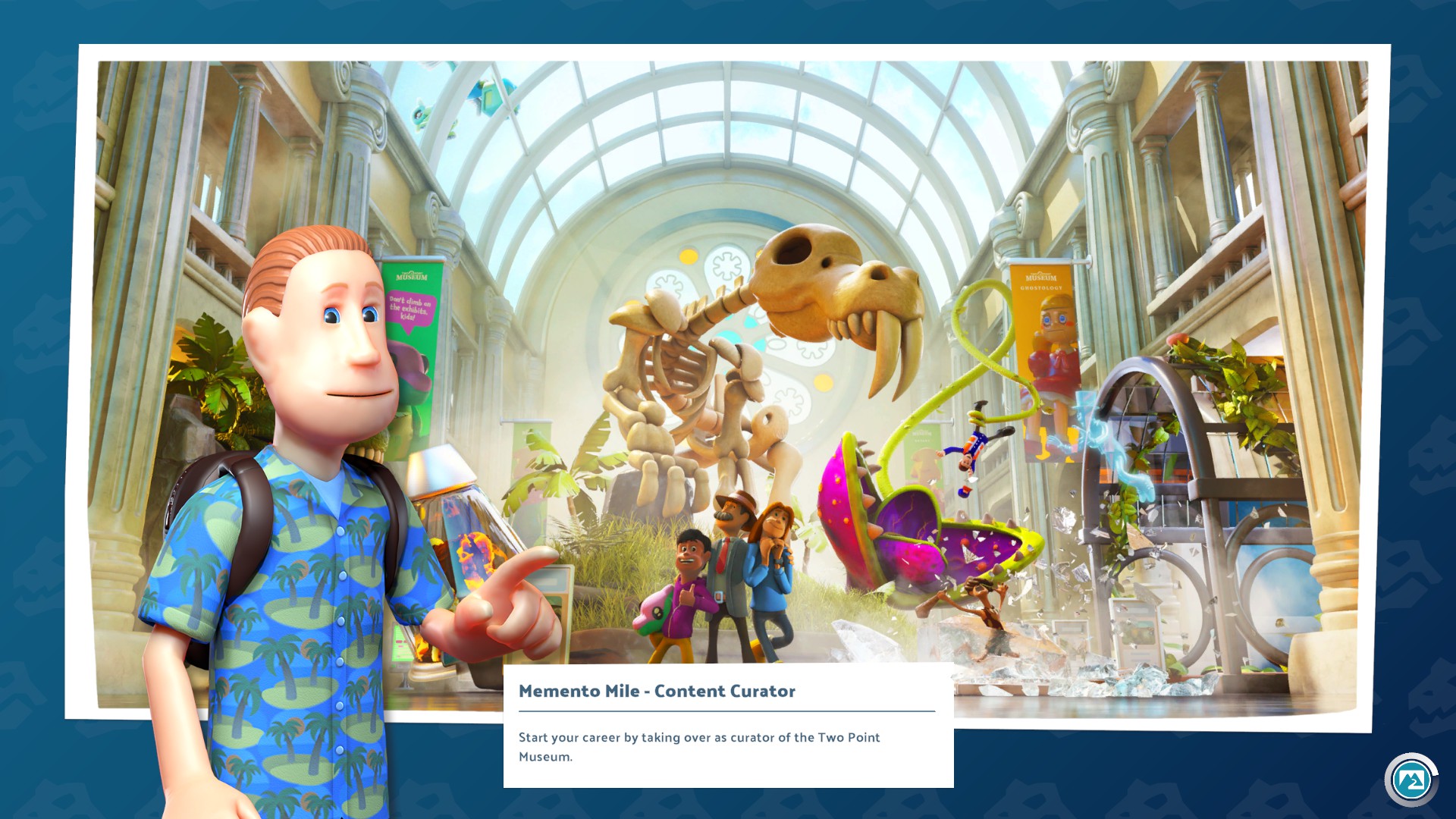

Is Two Point Museum the Most Accurate Video Game Depiction of Museum Work?

Kinda! Okay, so real life museum work doesn’t usually involve collecting poltergeists and we don’t often have groups of clowns regularly visit (at least, not in my experience). Two Point Museum (Two Point Studios, 2025) is obviously full of charming bits of nonsense that have been found throughout the simulation video game franchise. And yet,…

-

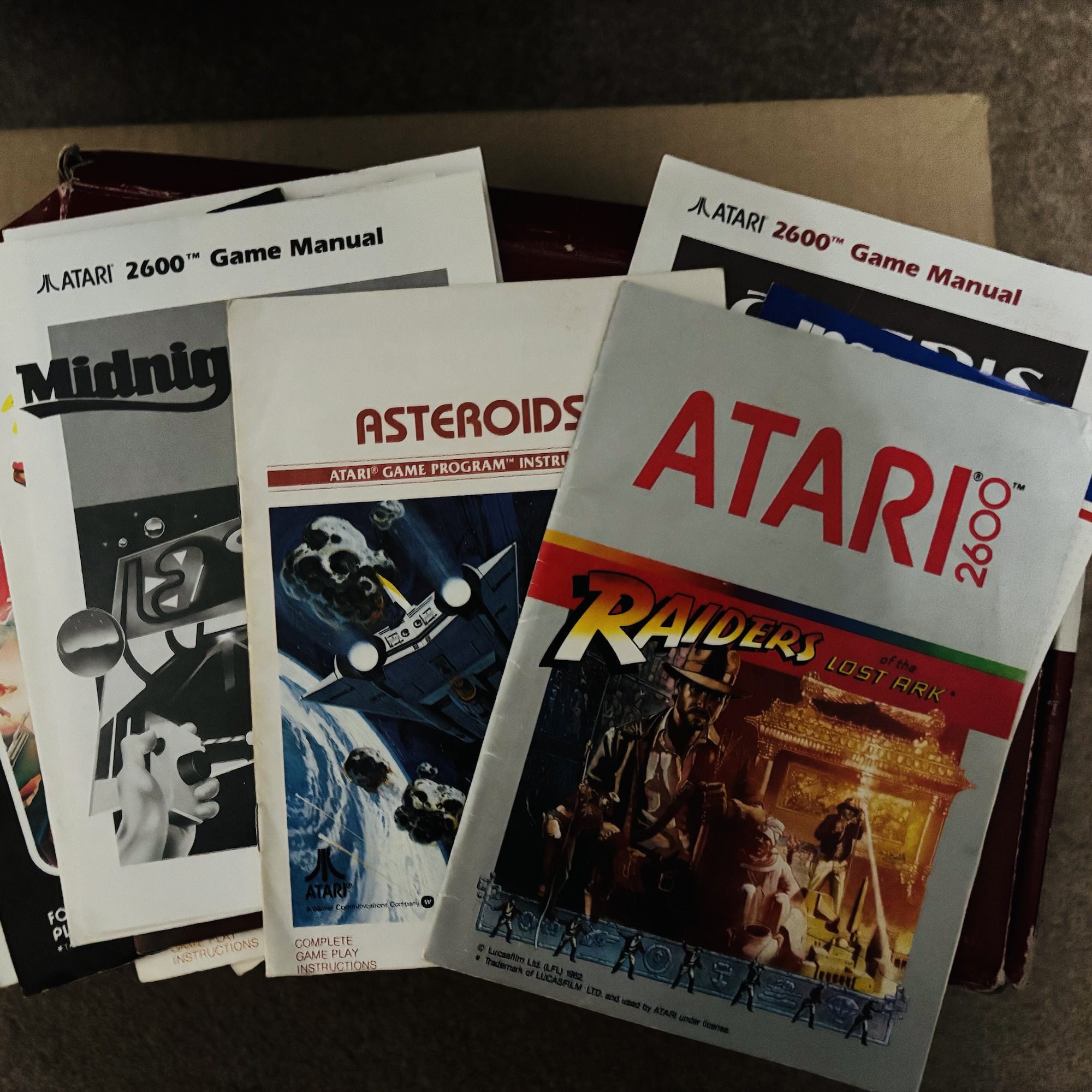

Archives are for the Gamers (and Everyone Else): Making Archives Available for All

This past Christmas, my dad gifted us an Atari 2600 from about 1982. Originally launched as the Video Computer System (VCS) in 1977, this compact console would eventually be renamed as the Atari 2600 in 1982, coinciding with the launch of the company’s new 5200 SuperSystem console (Lendino 2022). While we have no idea if…

-

Why Do We Love (Plastic, Inaccurate) Skeletons So Much? A Halloween Investigation

This blog post is part of the first ever Real Archaeology festival! Myself, along with several other archaeology-focused content creators, have come together to celebrate real, factual (not pseudoscience!) archaeology over the next few days, with new content coming out on a variety of themes. To see the full schedule and learn more about the…

Animal Archaeology

All things archaeology…but mostly dead animals.