This is a transcript from a talk I gave in April 2022 as part of the ARCHON workshop “Digging Archaeology through Social Media”.

Introduction

Archaeology still has a diversity problem.

It is difficult to find up-to-date demographic information regarding the archaeological workforce across the world, but the information that is available does not present a progressive image of the discipline. In the United Kingdom, for example, results from a 2020 survey revealed that only 3% of archaeologists are not white. In addition, only 18% identify as non-heterosexual, and only 11% consider themselves disabled (Aitchison et al. 2021). Data from a 2014 survey showed that among European archaeologists, only 1.1% considered themselves disabled (Aitchison et al. 2014). The last survey of the United States archaeological workforce indicated that only 2% identified as non-white (Zeder 1997); however, it should be noted that this survey was administered in 1994 and that there has likely been some progress, as the last survey for membership demographics in the Society of American Archaeology (2011) showed that 16% identified as non-white.

Although we can recognise that the field has become more diverse in comparison to prior decades, it is also painfully obvious how slow progress has been. There is a myriad of reasons as to why archaeology has been slow to diversify, of course – it can be difficult to get into the field to begin with, as many jobs require at least an undergraduate level degree. Universities themselves come with their own barriers as well, and not all of them will even offer archaeology as a degree. Even if you do find a place on an archaeology course, there are further barriers to gaining experience – for example, not all programmes will give you fieldwork training, and will expect you to pay separately for field school, which can often be prohibitively expensive. Once in the workforce, archaeology can be difficult to maintain employment in as well, with low pay and difficult working conditions in commercial sectors, and few tenure-track or otherwise stable positions in academia.

Outside of the logistics of working in archaeology, another issue that hampers diversity efforts is the lack of visibly representation – arguably the most well-known practitioners of the discipline (outside from fictional ones) with the biggest platforms are already well-represented individuals in the field: white, cis-heterosexual, non-disabled men. It is difficult for marginalised people to imagine themselves in a field that does not seem to have anyone else like them.

But perhaps the biggest factor that lends itself to such a lack of diversity in the field is that archaeology still maintains many problematic attitudes that can be traced back to its roots as a colonialist and imperialist endeavour. Archaeology is still seen by many outside of the field as a discipline empowered by looting and violence and has been weaponised in both the past and present to oppress and marginalise others. Unsurprisingly, this can be seen as a significant turn-off for marginalised people, particularly those who come from historically looted communities and formally colonised territories. Archaeology is seen as a very “white” field as well, not just in its lack of racial and ethnic diversity, but also in how little importance is given to non-white, non-western histories in the western/European institutions that serve as major epicentres for the discipline. On a more interpersonal level, problematic attitudes that serve to empower the notion that archaeology is only for white, cis-heterosexual non-disabled men are still prevalent through sexism, homophobia, queerphobia, transphobia, racism, ableism, and classism. These attitudes have historically shaped the way the field is practiced and taught and encourages problematic behaviours in the workplace as well – as such, it is difficult to imagine that the environment it creates is appealing to marginalised people.

Diverse Archaeology in Social Media

However, this issue of diversity and representation is slowly being tackled – particularly by the marginalised people in the field who are underrepresented. Perhaps the place where this is most apparent is on social media. As mostly accessible platforms in the digital space, social media has allowed for many underrepresented archaeologists to become more visible and express their perspectives and opinions in a medium without the restrictions often imposed by more “formal” methods of dissemination and communication. These formal platforms, such as academic journals, can also be seen as gatekeepers, often led by those who are already over-represented within the field whose biases shape the way archaeology is presented through publications. Social media, for the most part, lacks many of these institutional barriers, although this obviously lends itself to dangers in pseudoarchaeology and misinformation. But again, this means that those who do not fit the archetype of an archaeologist, as dictated by the problematic attitudes entrenched in the field, can actually find platforms for their unique voice and perspective that is sorely lacking in archaeology.

Such diversity among social media presence in archaeology can be separated into two main types: groups/accounts that are specifically dedicated to supporting and uplifting individuals from a particular marginalised identity, or individuals from certain marginalised backgrounds that are outspoken about their honest experiences in the field, and often discuss these experiences at length through a variety of mediums (e.g., vlogging, blog posts, podcasts). So although many social media accounts are specifically created to “represent” specific perspectives that are underrepresented in the field, others are simply speaking their truths in public. They are not asking to be seen as representatives of their particular background, of course, but by sharing their experiences and problems they have faced in the field, their input shapes the demands for archaeology to be better. Ultimately, their visibility on social media can serve as both evidence for the ways in which the field is lacking, as well as inspiration for others to strive towards success regardless; both of these outputs can potentially help in increasing the diversity of archaeology.

On social media, disabled archaeologists, for example, have been to amplify the need for a more accessible approach to archaeology and push for further consideration of accommodations as part of everyday archaeological practice. In the meantime, many disabled archaeologists have taken the initiative and created their own means for accessibility, using social media to promote them and lobby for wide adoption of similar practices – this includes Theresa O’Mahoney and the creation of the Enabled Archaeology Foundation, as well as Amelia Dall’s translation of archaeological terminology into American Sign Language. By promoting these practices via social media, disabled archaeologists are able to normalise the provision of accommodations and greater accessibility of archaeology as a practice and as a discipline.

For archaeologists who are part of the LGBTQ+ community, social media allows them to call out issues with regards to how sexuality is handled in archaeological interpretation and theory. In addition, social media allows for the creation of safe (digital) spaces for LGBTQ+ archaeologists to discuss their particular needs in the field, especially given the rise in hostility against LGBTQ+ individuals across the world. This includes advice for closeted or newly out individuals, as well as warnings against spaces that may be dangerous for them to work in. Organisations such as Queer Archaeology are able to not only act as a network for people working in queering archaeology (as a theory) to discuss ideas, but also provide support and resources to those who also identify as queer or otherwise LGBTQ+.

Similarly, there are many groups and organisations on social media for archaeologists of marginalised genders. Most are centred around women in archaeology, with TrowelBlazers being one of the most well-known organisations on social media for their work on promoting the work of women archaeologists who have otherwise been obscured by patriarchal interpretations of history. However, there has also been attention given to examining the issues faced by other archaeologists of marginalised genders, such as non-binary, gender-fluid, and gender-nonconforming archaeologists. Ultimately, these archaeologists have helped to bring more nuanced interpretations to conversations regarding gender in archaeology and how we view gender in the past, as well as call for further discipline-wide support in combatting patriarchal harm and violence in the field.

For BlPOC in archaeology, social media provides an opportunity to challenge the overtly white narrative of the past, especially with regards to histories of colonialism and enslavement. Having a platform on social media allows BIPOC to disrupt predominately white spaces and set the foundation for other racially minoritized archaeologists to enter the field, showcasing that archaeology isn’t just for white people. Their vital contributions to online discussions on racism in the field allow for white archaeologists to self-reflect on how their biases and actions may be perpetuating racism in the field and help push for a more anti-racist discipline.

Of course, these groups are not the only ones underrepresented in general discourse surrounding archaeology – other prominent individuals on social media have been able to express their experiences in being first generation academics, non-academics, volunteers, commercial workers, ex-archaeologists, hobbyists, and migrants. Social media allows anyone to discover what it is like to be an archaeologists from various regions, religions, and cultures, studying across different periods of time, different regions, different groups of people, and different materials. Archaeologists are able to tell their own stories and experiences and showcase how varied the world of archaeology can be.

My Social Media Story: Breaking the Archaeologist Archetype

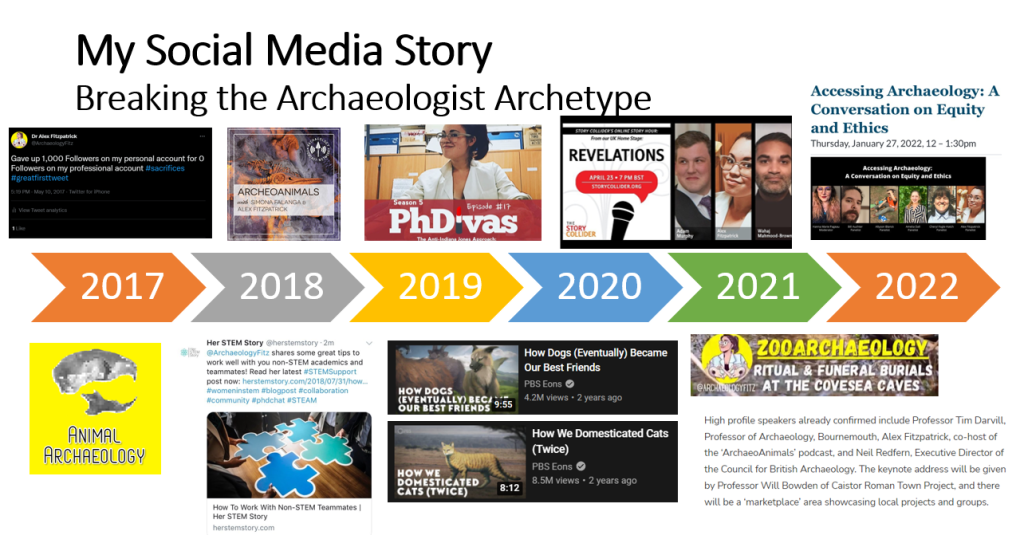

Social media has also played a significant role in my development as an archaeologist as well. In 2017, only four months into my PhD, I had a nervous breakdown that lasted for another few months and completely disrupted my studies. After receiving the medical help I needed, I realised that I needed to make up for lost time and decided that perhaps the best way to do so was to “get myself out there” and create a Twitter account specifically for promoting my research. At the same time, I also started a WordPress website and Instagram – I wanted to create as much of a presence as possible, knowing that I was already at a disadvantage in British archaeology as a queer, disabled Chinese American migrant woman and that I would ultimately need to make my own opportunities if I wanted to find any form of success in the field.

I will admit that it took a while to find my own voice on social media – I mostly wrote about basic things about zooarchaeology and updates on my PhD studies. But around 2018, I developed more confidence in my ability to express myself and my opinions, leading to more blog posts and Tweets on more serious and personal topics, such as racism, ableism, and immigration. Finding my voice was arguably the most important part of my journey as an archaeologist, as I not only was able to realise that I had the skills to write in a way that was accessible to non-specialists, but that I could also tackle serious and complex topics and convey them in a nuanced manner. This visibility has ultimately led to many opportunities – in 2018 I was asked to create a zooarchaeology-themed podcast for the Archaeology Podcast Network, and since then I have also been invited to write articles for various websites, speak at events, and even won awards for content I’ve created for YouTube and for my blog.

Of course, there has been some downsides to having a social media presence. During my PhD studies, there was often concern from my supervisors that my outreach and communication work on social media was a distraction from my actual research. And I also experienced extensive harassment from others, including racist and sexist comments on Twitter and on my website, as well as threatening emails from strangers. But despite this, social media has always been vital to my development as an archaeologist and has only increased in its importance as I move outside of archaeology due to the lack of employment opportunities. I still want to remain in the field, of course, but in the meantime, I am happy to be able to still engage with archaeology through social media.

Social Media Solutions: Is It Worth It?

So, with all of these examples in mind, we come to the final question – is social media a worthy tool for diversifying the field? On one hand, social media is relatively accessible, in that it is often free and relatively easy to use if you have an Internet connection. Although building up a following and developing an audience will take time and dedication, it can be done through social media without the need for dealing with disciplinary gatekeepers who do not share the same priorities as you and your community. In addition, social media allows for you to not only connect with people from across the world, but also make relationships and potentially develop an invaluable support network. You can also find your own community online, consisting of others with similar experiences who can provide support and comfort when you may be feeling otherwise isolated in the field. By becoming more visible online, you may eventually find yourself acting as a source of inspiration for others from similarly marginalised background, continuing a cycle of increasing diversity. More practically, a social media presence can lead to opportunities for further work – this may include collaborations with other social media accounts, consideration for projects, and invitations to participate in events. And perhaps most importantly, once you have achieved a formidable following, you can act as a voice for change and bring further attention to issues in archaeology that those who are already well-represented in the field may not have been able to identify.

On the other hand, social media is not accessible for everyone – not only from a disability perspective (e.g., transcriptions, captions, alternative text), but also with regards to language barriers as well. In addition, there is still a significant amount of digital poverty throughout the world. As such, this creates biases in who actually has access to the Internet, which is furthered by the biases in what sort of content gets popularised online – often English language content, from the West, or at least from the Global North. Perhaps the biggest risk in increasing your visibility online is the fact that you may be left open to increased harassment from others, especially strangers. Although there a mechanisms in place across most social media platforms to deal with negative comments and trolling, there is still risk for more harmful forms of harassment, such as having private information revealed online. Finally, it should be noted that there is still a degree of stigma associated with social media, particularly among senior professionals and academics – many still do not take social media seriously as a form of dissemination and communication and may even look down upon those who utilise it as part of their professional persona. Although these attitudes seem to be changing given how many projects and institutions now focus resources on their social media management, it is still apparent that not everyone in the field considers social media to be something worth investing time or expertise into.

Ultimately, social media is a platform, and as such it comes with the risks involved whenever you decide to publicly present yourself. However, if used wisely, social media can not only help promote yourself and your work but empower you to push for tangible change in the field and make archaeology more equitable for everyone.

Social Media Solutions: Diversify Your Feed!

So, how can you utilise social media to both promote and support a more diverse archaeology? The answer depends on your positionality and power within the field. For those of you who are already well-represented in the field, my advice would be to follow those from backgrounds different from yours – this includes groups and projects dedicated to sharing and exploring different perspectives on archaeology. In exposing yourself to differing opinions and experiences in the field, you can begin to do some self-reflection on how your own experiences may already be well-represented in archaeology, and how these experiences may turn into biases that effect your interpretations and research. Similarly, consider how much space you take up in archaeological discourse, and determine if you have the ability to provide a platform to someone more underrepresented in the field – for example, you could retweet material from someone else with a smaller follower count, lets someone else take over your account for the day and use your platform for their needs, or even sponsor and/or organise online events that centre marginalised people and promote it on your account. In addition, if important conversations are occurring online, instead of immediately jumping in with your opinion, you can stop and reflect on whether or not you could instead uplift the voice of someone else who is more relevant to the discourse. Perhaps most importantly, you should think of how to translate your online allyship into tangible support and promotion of underrepresented people outside of social media.

For those who are from marginalised backgrounds, my advice would be to find your people first. As I previously mentioned, my own experiences in developing my social media presence would have ended prematurely due to isolation and harassment if it wasn’t for the friendships I made, as well as the broader support network I’ve developed with archaeologists from similar backgrounds and experiences. In addition, it is useful to find organisations and groups that are dedicated to supporting certain marginalised backgrounds – not only can they provide resources and advice, but there could also be opportunities there to volunteer with them and further increase your visibility in the field as part of a larger group. In developing your approach to social media, you should also think about what you want to represent – are you focusing on your research and work in archaeology? Do you want to present the viewpoints and experiences of people with your background? Although it is not necessary to have a “niche”, it is useful with regards to how you want to present and market yourself and your social media persona. You should also consider what your expectations are for developing an online presence – are you aiming to spread awareness, or developing a gigantic following? These things will take time, so don’t be discouraged! But also recognise that any goals or expectations you may have will require dedication and time, so plan accordingly. In the meantime, try and take as many opportunities as you have capacity for – even if it is something as small as writing a guest blog post, opportunities that allow you to expose yourself to other audiences are vital in developing a following. And finally, don’t be afraid to speak your truths online – by being honest in our experiences in the field, we can identify the areas in need of further work and growth. But at the same time, you need to recognise your own personal boundaries and where you feel most comfortable in taking risks.

Social media is not a magical solution to all of archaeology’s problems, of course, and there is much to be done to make the field more progressive and inclusive. However, social media can be a powerful tool for change, if used correctly. As archaeologists, we need to accept the vital role that social media plays in our everyday lives, as well as the influence it wields over society and culture today. Archaeology must adapt with the changing times if it wants to survive as a discipline – and that may include learning exactly what a “TikTok” is.

References

Aitchison, K., German, P., and Rocks-Macqueen, D. (2021) Profiling the Profession 2020. Landward Research Ltd.

Aitchison, K., R, Alphas., V, Ameels., M, Bentz., C, Borş., E, Cella., K, Cleary., C, Costa., P, Damian., M, Diniz., C, Duarte., J, Frolík., C, Grilo., Initiative for Heritage Conservancy., N, Kangert., R, Karl., A, Kjærulf Andersen., V, Kobrusepp., T, Kompare., E, Krekovič., M, Lago da Silva., A, Lawler., I, Lazar., K, Liibert., A, Lima., G, MacGregor., N, McCullagh., M, Mácalová., A, Mäesalu., M, Malińska., A, Marciniak., M, Mintaurs., K, Möller., U, Odgaard., E, Parga-Dans., D, Pavlov., V, Pintarič Kocuvan., D, Rocks-Macqueen., J, Rostock., J, Pedro Tereso., A, Pintucci., E.S, Prokopiou., J, Raposo., K, Scharringhausen., T, Schenck., M, Schlaman., J, Skaarup., A, Šnē., D, Staššíková-Štukovská., I, Ulst., M, van den Dries., H, van Londen., R, Varela-Pousa., C, Viegas., A, Vijups., N, Vossen., T, Wachter., and L, Wachowicz. (2014). Discovering the Archaeologists of Europe 2012–2014: Transnational Report. York Archaeological Trust.

Society for American Archaeology. (2011). 2010 Needs Assessment Survey. Association Research Inc.

Zeder, M. A. (1997). The American archaeologist: a profile. Rowman Altamira.

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can find my PayPal here.