Okay, I mean…technically the Witcher is more of a zoologist with a bit of forensics training, but let me shoe-horn in my expertise please!

After years of being yelled at to play the Witcher 3: the Wild Hunt (2015), I am finally playing the Witcher 3: the Wild Hunt (round of applause please). And I’m enjoying it a lot, as it fills the fantasy void within my heart that the Dragon Age series has left. But the gameplay mechanic that interests me the most is, unsurprising, the investigation sequences during the Witcher contracts.

Geralt, the main character, is a Witcher (have I written that word enough yet?). This means he’s been trained and physically & genetically enhanced in order to combat monsters and other deadly creatures.

Geralt, the main character, is a Witcher (have I written that word enough yet?). This means he’s been trained and physically & genetically enhanced in order to combat monsters and other deadly creatures.

So, what do I mean that Geralt is basically a trained bioarchaeologist? Well, one of the many types of quests you can get during the game are called “contracts”, which are basically paid jobs, usually involving the defeat of some creature that’s terrifying the local populace. But it’s not just about riding off and fighting a griffin or an ogre…there’s a bit of investigation involved as well.

During these quests, Geralt is usually directed to a site where some horrible thing has happened – a peasant has been horribly murdered, or a person has gone missing and only left behind a blood trail, or maybe it’s just the whispers of local folklore that’s brought him there. Whatever it is, Geralt will begin to investigate and look for clues; these will come in the form of animal tracks, bloodstains, or even the deceased themselves.

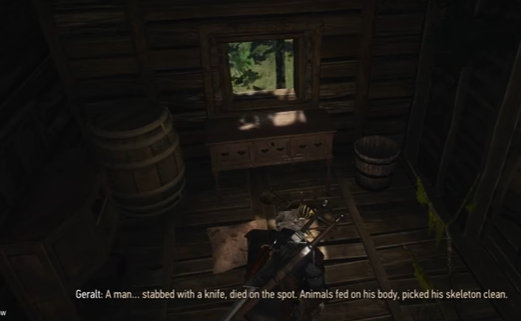

Again, most of these interactions are probably more forensic in nature, but there’s still lots of similarities with bioarchaeology. For example, Geralt has an incredible amount of knowledge of common taphonomic processes (which I’ve actually written about here, except in a different video game). Taphonomy refers to the processes through which a living being undertaken as they move from living to being part of the archaeological record as a post-mortem deposit (Lyman 1994).

When Geralt looks at remains, he can deduce the actions that occurred to cause that particular deposit – did they die here, or were they placed here after death? Has any animals moved or otherwise affected the body in any way? What about the environment – has weather affected these remains in any way? Is there something significant about the way this body was or was not buried?

And these are important questions to ask about archaeological deposits as well! It isn’t assumed that we are looking at an intentional grave, as many factors could have led to this particular deposition – were they buried here intentionally, as a “final resting place? Were they first placed somewhere else and then moved here? Was the body modified in anyway prior to this eventual deposition? This can include not just other humans, but other animals and environments factors.

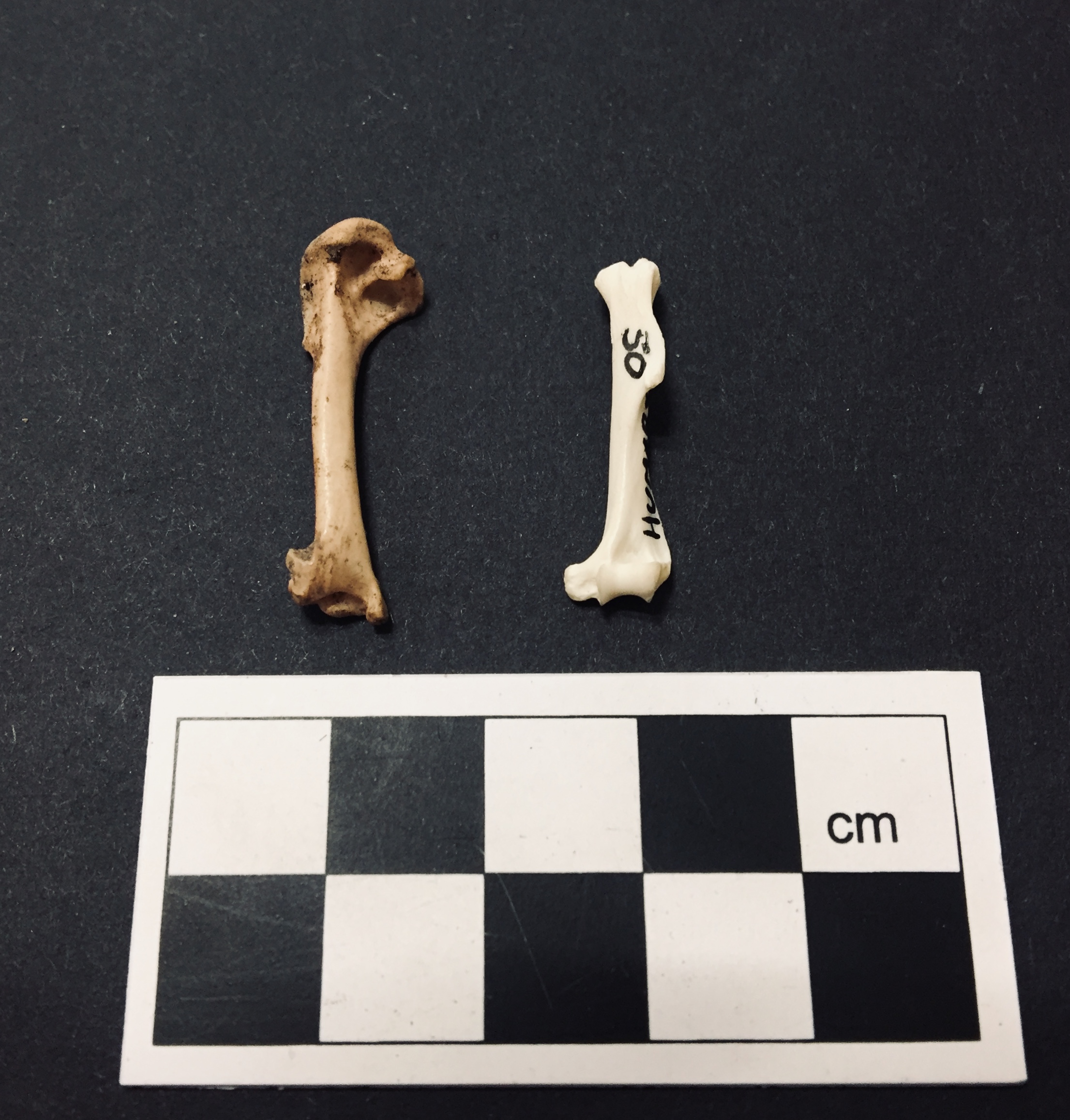

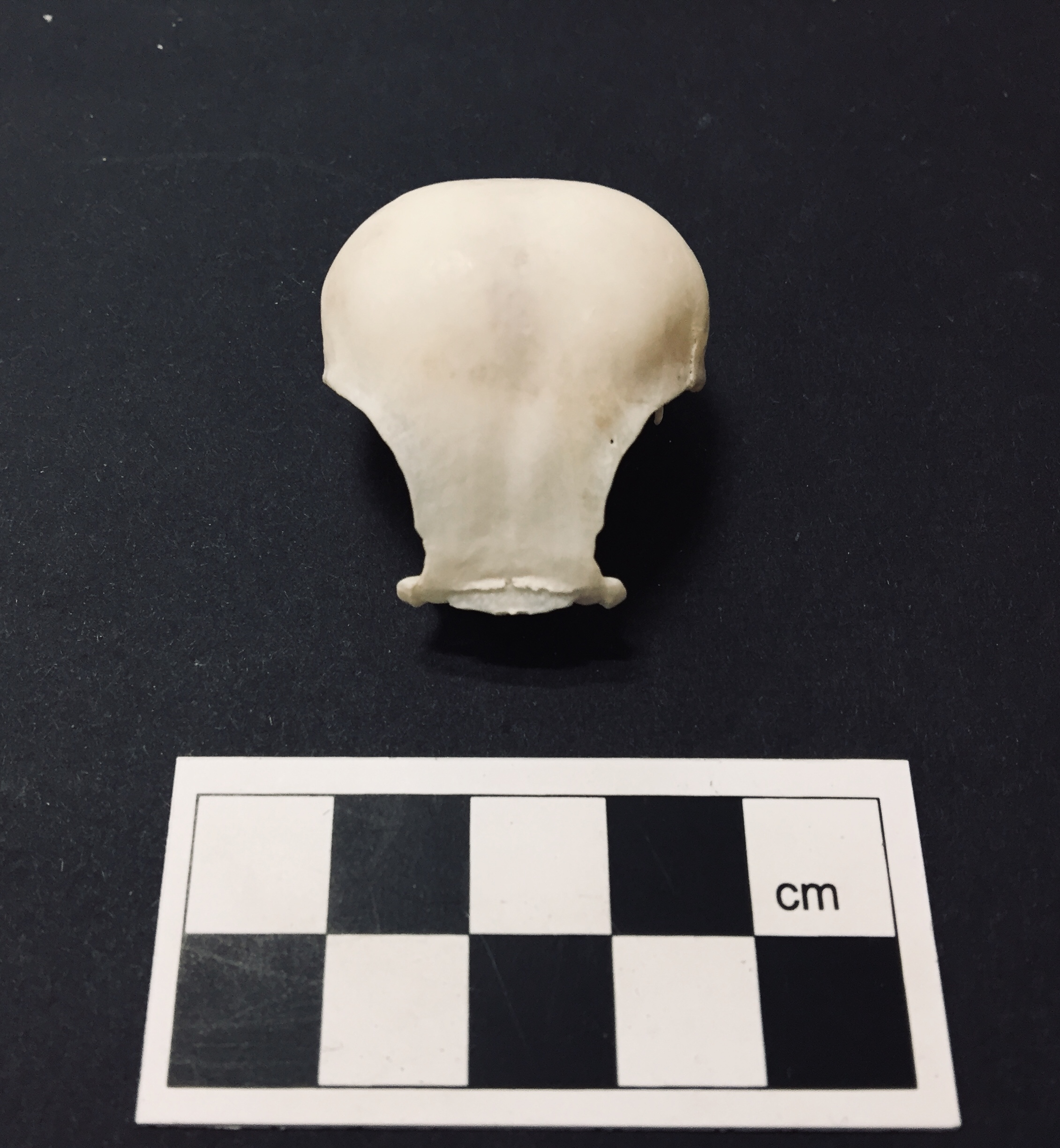

But more specifically, Geralt is a walking bestiary – he knows not only how to recognise and identify faunal remains, but also understands their living behaviours as well. When Geralt comes across the remains of a slain griffin, he immediately makes the connection that the one he has been hired to kill was the deceased’s partner – but how? Well, he understands the mating behaviours of griffins!

And, as a zooarchaeologist myself, I really enjoy seeing how extensive Geralt’s zoological knowledge is and how he incorporates it in his interpretations alongside his observations and evaluations of the surrounding environment. Why? Well, to quote Diane Gifford-Gonzalez (1991), “bones are not enough”!

Being able to identify animal bones is a vital skill, but it’s not just the end of zooarchaeology. Knowledge of behavioural studies, of regional geology, climate and environmental studies…these can all be utilised and factored into an interpretation, allowing for an interdisciplinary and more dimensional narrative for the assemblage at hand.

Now, if only I can hire a Witcher to take a look at my current faunal assemblage…

References

CD Projekt (2015) The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt.

Gifford-Gonzalez, D. (1991) Bones are Not Enough: Analogues, Knowledge, and Interpretive Strategies in Zooarchaeology. Anthropological Archaeology 10. pp. 215-254.

Lyman, R.L. (1994) Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can donate here.