Content Warning: Photo of human remains included in this post.

In Skyrim (Bioware 2011), capital punishment usually consists of a swift beheading – this is seen in the game’s opening, where you watch as a Stormcloak, deemed to be traitorous to the Empire, is beheaded by the Imperial army’s executioner. You luckily manage to escape the blade thanks to a dragon, but a similar execution is stumbled upon again in the town of Solitude.

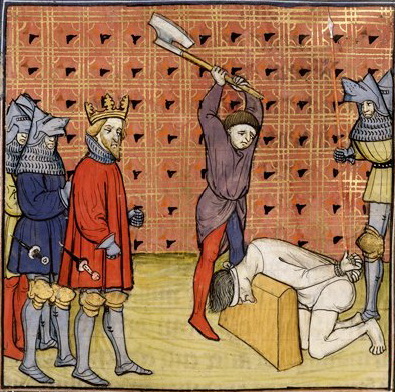

In real life, decapitation has been a form of capital punishment for ages, with archaeological evidence of intentional beheading dating back to the later prehistoric – although it can be argued that some instances could have been part of ritual sacrifice as well (Armit 2012). Decapitations in antiquity (read: ancient Greece and the Roman Empire) were often used for citizens, especially of higher status, as it was seen as a more humane and less dishonourable punishment. This would possibly be accurate if the executioner was skilled and could deliver a quick and clean decapitation in a single blow of the sword or axe. This would change, of course, with the popularisation of the guillotine for beheading (Clark 1995).

The British history of decapitation as capital punishment goes back centuries and is too long to properly discuss in a blog post. Anglo-Saxons originally used decapitation to punish more serious offences of theft, but eventually this practice was reserved for those of noble and high status who have committed acts of treason (Dyson 2014). Arguably the most famous cases of beheading in Britain belongs to Catherine Howard and Anne Boleyn, two of King Henry VIII’s many wives. These executions were part of the seven that were done privately in the Tower of London (Clark 1995).

Decapitation is still used as capital punishment in some places to this day, but has mostly been abandoned as a practice in most parts of the world, although only relatively recently – for example, it was still used for capital punishment up until 1938 in Germany (Clark 1995).

So, how do we discover decapitations archaeologically? Isn’t it common to find skeletons disarticulated (or not together) once excavated? How do you differentiate between skulls from the beheaded and skulls from the dead?

Evidence of decapitation can sometimes be seen spatially, through the methods and locations of burial. In some places, such as Roman burial sites, there were no observed difference between decapitation burials and more normative burials. In the later Anglo-Saxon period, however, decapitation burials were moved to “execution cemeteries” to reflect a cultural understanding of decapitation as a “deviant burial” that should be kept separate from other burials (Dyson 2014).

The best place to look for evidence for decapitation is on the vertebrae – a beheading that has been done correctly will usually leave cut marks on the cervical vertebrae, which make up the neck. More unfortunate decapitations that required several more blows for a successful separation will also show related cut marks on facial features, such as on the mandible (Carty 2012).

References

Armit, I. (2012) Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Carty, N. (2012) ‘The Halved Heads’: Osteological Evidence for Decapitation in Medieval Ireland. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology.

Clark, R. (1995) The History of Beheading and Decapitation. Capital Punishment UK.

Dyson, G. (2014) Kings, Peasants, and the Restless Dead: Decapitation in Anglo-Saxon Saints’ Lives. Retrospectives. University of Warwick. (p. 32-43)

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can donate here.