Note: This is part of a book chapter I wrote a few years ago for a now-defunct project. After a few attempts to submit it to several journals, I gave up on it. I recently brought it out to aid in the writing of a new paper and figured it might be worth posting it on the blog. Nearly four years later, I don’t think its a particularly great piece (and, rereading it now, I understand what Reviewer #2 meant when they called me a ‘obviously angry early career researcher’ lol), but I felt like it could do with seeing the light of day in some form. I also think it’s a nice look into a particular struggle I was having internally at the start of my PhD. So bear in mind that this isn‘t necessarily up-to-date, but I think the general theme of it still remains relevant.

This Paper is a Confrontation

Archaeology is, and always has been, a violent discipline.

This statement may be considered “combative” and “confrontational” in tone, but this is intentional. This paper is a crucial confrontation for our discipline that is long past due. Although there is certainly more self-critique and reflexivity in archaeological literature today (Nicholas and Hollowell 2007; Fiskesjö 2010; Fontein 2010), to say that archaeology as a whole has sufficiently dealt with its considerable baggage would be inaccurate; on the contrary, issues brought up by the relatively recent movement towards academic equity and the decolonization of the academy seem to have simply caused more arguments amongst our peers. One pertinent example is the question of repatriation of stolen artefacts from colonised lands, which is still a topic of debate (Burke and Smith 2007; Jenkins 2016; Thomas 2016).

The impetus of this paper is slightly drawn from my own personal confrontations. As an undergraduate student who had registered for my first archaeology course, I was understandably quite excited. So excited, in fact, that I immediately posted about it on social media, claiming that I was on my way to become “the next Indiana Jones”. My excitement was slightly cut down by a comment left by a stranger on the Internet: “why would you celebrate becoming part of an imperialist field?” Over the past decade, I have thought about that comment and attempted to reconceptualise my role as an archaeologist alongside my newfound consciousness of social justice and activism.

What is needed (and what is necessary) for archaeology to progress and grow into the future is the acceptance of a hard truth: that in both theory and in practice, our discipline as it is carried out today necessitates violence. That, regardless of intention, archaeologists will continue to cause harm in the name of science, under the assumption that physical and socio-cultural damage is outweighed by the academic gains and insight from archaeological research. This paper is a wake-up call for archaeologists to truly understand the costs of our actions – and perhaps think about ways in which we can radically change direction moving forward as a discipline.

Archaeology is a Violent Act

Physically, archaeological excavation and analysis necessitates violence on some level – whether it’s the first penetrative blow against land to create a trench, or the destruction of material remains within a lab for the sake of “science”, archaeologists can be seen as purveyors of constant destruction in the search of our collective past. I refer to this form of archaeological violence as a “violent act” to emphasise the physicality and tangibility of these actions.

Perhaps the best place to start with this critical analysis is with possibly the most definitive aspect of archaeology: the “dig”. Excavation, by its very nature, requires a varying amount of destruction of the surrounding environment: trowels, shovels, and mattocks are used to break beneath the ground, modern landscapes are dramatically levelled and altered to force the past out from its undisturbed slumber, and remains (both material and otherwise) are often ripped from their final resting places for further analysis and curation. Earlier approaches to excavation could often take the concept of “destruction” to another level, like Heinrich Schliemann’s infamously careless use of explosives during his excavation at Hisarlik (Allen 1999: 146).

In recent years, archaeologists have become more conscious of the violent tendencies of their handiwork, although it should be noted that this is cited mostly as an environmental or conservational concern (Matero 2006; Caple 2008; Holtorf and Kristensen 2015). Non-invasive fieldwork is not necessarily new, but recent advances in technology have allowed these non-destructive methods of surveying sites to be utilised more consistently and with better accuracy (Corsi 2013). These methods include geophysical survey (Gaffney 2008), remote sensing (Challis and Howard 2006), and, more recently, digitisation and 3D visualisation (Caggianni et al. 2012; Torrej ón et al. 2016). Despite these advances, it should be noted that some invasive methodology, like traditional excavation, remains a “necessary evil” for most archaeologists.

Of course, destruction in the name of archaeology is not limited to just excavation; the post-excavation stage of archaeological fieldwork can be just as destructive, albeit on a physically smaller scale. Many analytical methods of archaeological science require the partial or total destruction of samples as part of the process; this includes methods such as stable isotope analysis and various dating methods, such as radiocarbon dating (Mays et al. 2013).

Again, archaeologists today are becoming more concerned with non-invasive methodologies for scientific analysis, especially as many samples are exceptionally fragile and already at the mercy of contamination and degradation from relocation to the lab environment (Bollogino et al. 2008; Crowther et al. 2014). Alternatives to destructive sampling include x-ray techniques and spectrometry, both which can be applied to a wide variety of materials (Adriaens 2005; Uda et al. 2005).

As archaeology continues to progress and grow alongside advances in technology and science, it is likely that we will soon find ways to substantially limit the amount of physical destruction. However, I’d argue that the impetus behind much of the non-destructive methodology movement is more based on conserving the material culture, rather than respecting the cultural heritage behind the physical artefacts. That archaeologists may not consider the cultural significance behind sites and artefacts when deciding whether or not invasive methodology is necessary for analysis leads us to the less tangible form of violence that has been inherent in archaeology from the beginning.

Archaeology is an Act of Violence

Archaeology is violent on a socio-cultural level. As a discipline rooted in colonialism and white supremacy, archaeology is complicit in perpetuating acts of violence against BIPOC communities: from the theft of countless artefacts from colonised lands that are still held hostage by their colonisers in prominent institutions, to the dehumanisation of bodies of colour that are propped up for display in museums, treated as educational objects rather than people, archaeology continues to allow itself to be weaponised for the sake of maintaining the current status quo through the oppression of others. This form of violence is specifically referred to as “acts of violence” to further emphasise that these are conscious acts that are imposed on others, more often than not as a form of marginalisation.

Let’s first start at the beginning of our discipline; it would not be an exaggeration to say that early archaeological pursuits were colonialist in nature. Egypt is arguably the region most associated with early, pith-helmeted excavations, resulting in a sizable amount of cultural theft through early (European-led) archaeology. One of the largest organised expeditions through Egypt was born through Napoleon’s military occupation during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a formidable display of how imperialism is so often intertwined with fieldwork and research. The French expedition led to the discovery of Rosetta Stone and the publication of Description de l’Egypte, ultimately giving birth to the modern field of Egyptology (Reid 2002: 31-33). The defeat and withdrawal of French forces at the hands of the British let to the latter’s seizure of all artefacts collected by the former, including the Rosetta Stone (Wallis Budge 1989); this can be seen as the start of British theft and looting of Egyptian cultural heritage, which continues with the financial control of later archaeological excavations and museums in Egypt that allowed for various “relocations” of artefacts (Riggs 2013).

This pattern of recontexualising colonial expeditions as “research adventures”, erasing the violence made against Indigenous populations and replacing it with the excitement and thrill of Western settlers’ adventuring across so-called “undiscovered” lands (Tuhiwai Smith 2012), may be best summed up as “colonial curiosity”. I believe this term accurately displays the dichotomy at play: that we have the propagandised, revisionist version of these expeditions as curious adventurers and knowledge-seekers “saving” artefacts and information from foreign land, and the actuality of colonialism in practice.

Colonial curiosity is, of course, not just restrained to the African continent. In North America, many settlers and their descendants today have stories of finding arrowheads in their backyard; my own father, a settler occupying Massapequas territory (Long Island, New York), often spoke of his childhood collection of arrowheads whenever we spoke about my archaeological research. It speaks volumes that what amounts to heritage theft is so normalised as part of the North American settler upbringing. Most famously, Thomas Jefferson practised his own form of amateur archaeology when he dug up Native American graves just for his own personal satisfaction and curiosity (Riding In 1992: 15-16).

Even today, the idea of the archaeologist as the “dignified looter” has become so entangled with the general public’s conception of the profession that most, if not all, representations of archaeology in pop culture are no more than just thieves with academic certification and institutional funding – and while many of our colleagues may bristle at the constant comparisons between our work and that of the imperialist looter and adventurer Indiana Jones, can we truly say that archaeology is so far off from this description?

The repatriation debate highlights perhaps the most unfortunate and consistent recipients of archaeological violence today: the dead. Repatriation is a process by which human remains (and occasionally material culture) are returned to the communities from which they originate in order to be reburied. In most cases, these remains have been housed in museums and institutions to be employed in research and analysis (Hubert and Fforde 2002: 1); in essence, repatriation is a demand that human remains are no longer dehumanised and removed from their cultural and spiritual contexts. Calls for repatriation have been led by Indigenous peoples in North America (Thornton 2002; 2016) and Australia (Turnbull 2002; Byrne 2003), although there are numerous repatriation demands from communities around the world (Schanche 2002; Hole 2007; Shigwedha 2016). Over the past few decades, repatriation has become a legal issue as well, as laws such as the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the United States provide more stable ground for repatriation claims. It should be noted, however, that laws such as NAGPRA are not the “end-all” solution to finally solve the repatriation question – there are still many opponents of the act that continue to push back against it, while proponents have also acknowledged that it is still an “awkward compromise” that places a huge emotional and financial burden on Indigenous peoples (Nash and Colwell-Chanthapohn 2010).

Opponents of repatriation may see themselves as guardians of knowledge or forerunners of archaeological progress, but who are they from the perspective of those calling for repatriation? At worst, they are thieves who are holding ancestral bodies hostage in their archives and laboratories. And at best? They are guilty of dehumanising these ancestors, seeing them more as objects for analysis rather than people who once lived and breathed. It’s this perspective that I think some archaeologists and curators may neglect to consider and empathise with, which may explain why there is still a debate regarding this issue.

The most well-meaning archaeologist may still be inadvertently continuing the discipline’s tradition of colonialization through smaller actions, particularly within the academy. In the United Kingdom, for example, despite a significant increase of women in academic and commercial archaeology, the field is still comprised of 99% white professionals (Hamilton 2014). The domination of archaeological literature by white and European academics has created an example of a phenomenon sometimes referred to as Chackrabarty’s Dilemma within the field, where non-European, marginalised academics researching their own cultures and archaeologies must inevitably turn to European literature which poses a risk of replicating Westernised biases and assumptions, creating a cycle of continued marginalisation (Chakrabarty 1992; Langer 2017: 191).

Colonisation by citation is unfortunately a common phenomenon. By continuing to uphold white voices over BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour), the narrative will remain under the control of Western/European theory and practice. However, there has recently been more pushback against the overt whiteness of citations; initiatives such as the Cite Black Women movement have rallied to decolonise academic citations across all disciplines (Jackson 2018). These BIPOC-led movements are absolutely vital and necessary, but they are just the beginning of the sort of radical change necessary for a just and equitable academy.

Intertwining, Destructive Acts

We have now examined archaeology as both a violent act and an act of violence, but note that these two concepts should not be considered as in opposition with each other; archaeological violence is often more complex, where violent acts and acts of violence are intertwined. To anticipate one critique of this paper, let me elaborate on why we must consider the seemingly impartial violence of physical acts of archaeology alongside the more overtly and intentionally malicious violence of colonialism. This conversation of “intent versus impact” is prevalent in discussions of hate speech, where the bottom line is: when the impact of your actions causes harm and aids in the further marginalisation and oppression of others, then your intent does not matter (Utt 2013).

These forms of violence can be analysed as separate entities, but in reality, they cannot be separated from each other so easily – as long as archaeology retains its violent nature, there will always be this assumption that heritage (both tangible and otherwise) will need to be destroyed in some way for “progress”. Arguments about the “greater good” in archaeology bring up unfortunate comparisons with similar excuses made in the name of controversial sciences like eugenics – which is fitting, given that archaeology also has a history of being utilised in theorising eugenics (Challis 2013).

There are numerous – perhaps too many – examples of intertwining acts of archaeological violence. The excavation (and inevitable destruction) of sacred sites, like the controversial destruction of Tikal Temple 33 (Berlin 1967) is a physical reminder that Indigenous religion is one of the many targets of colonial violence (Carey 2011: 79-83). Ultimately, we cannot have one without the other – violence begets more violence.

A Non-Violent Archaeology, A Transformative Archaeology

With the violence of our discipline acknowledged, we are left with an imperative question: how can we, as archaeologists complicit in institutional destruction and oppression, do better? First, another truth that we must consider: we cannot simply “undo” the damage that archaeology has caused. Actions and initiatives such as repatriation and increased disciplinary diversity are not “cure all’s” that will absolve archaeology of its sins, although they are certainly necessary steps in the right direction. We can return remains of the ancestral deceased and acknowledge our complicity through texts and actions, but we cannot claim that these deeds mend the wounds that centuries of violence have created.

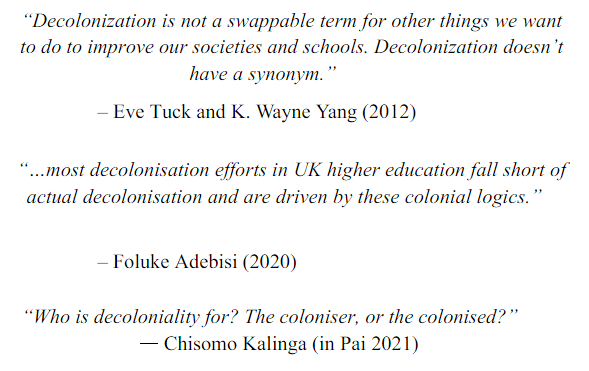

So if we cannot undo the damage, then what is the alternative for archaeologists? I believe archaeologists have the capacity to radically change our discipline into what I would refer to as “transformative archaeology”. This form of archaeological practice and theory would draw heavily from ideas of transformative justice theory, which is a method used to address longstanding legacies of violence through (Gready and Robins 2014: 339). Transformative justice theory itself has its roots in transitional justice, which also addresses violations of human rights, but within the confines of the current legal and political systems (Nagy 2008: 276). In contrast, however, transformative justice pushes past the limitations of transitional justice, emphasising the need to completely transform the systems we are working within in order to meet the needs of the oppressed at the forefront and provide them the agency they have long been denied within the current systems (Gready and Robins 2014: 350-355). Although transformative justice is usually associated with activism and human rights discourse, there is precedence for academic applications. Transformative paradigms allow researchers to work with greater reflexivity rather than complicity, as they not only acknowledge the realities that construct the context within they work in, but also has tools built into these paradigms for researchers to be more ethical in making decisions and conclusions (Mertens 2007).

Theories aside, what would this mean for how we engage with archaeology? If we are to move beyond colonialist archaeologies, we must also move beyond just theorising and put these critical conversations into action (McDavid and McGhee 2010: 481). To start, I would argue that a transformative archaeology would need to be non-violent by nature; archaeological violence is just too entwined with colonialism and racism to continue to support it as the crux of our discipline. Instead of centring excavation as a standard within archaeology, a transformative version would encourage more communal approaches that place the needs of descendent and affected communities over the goals of general archaeological fieldwork. We would need to establish a sense of collaboration that cannot necessarily coexist with the power dynamics inherent in modern archaeological practice; for this, adopting non-hierarchical approaches to organisation from anarchist theory may be the most suitable approach (Fitzpatrick 2018). Perhaps the easiest way to accomplish this is through dialogue with the communities most affected by our archaeological research, where we allow said communities to assert their agency – and their authority. When working as a postcolonial practice, archaeologists must give up the notion that our interpretations are the only interpretations; we must concede authority to descendent communities (Battle-Baptiste 2010: 388). It should also be noted that a transformative archaeology would not completely remove destructive methodologies from our oeuvre; instead, we embrace this act communally with others, allowing for decisions to be made collectively and with the understanding of the community as a whole. It is a violent act, and perhaps one of the few remnants of the overtly violent archaeology of the past, but by giving communities agency and sharing the responsibility through conversation and organisation, we can lessen the more socio-cultural harm it creates. Overall, archaeologists need to embrace the subversion of normalised power structures as part of a transformative archaeology. Through this, we may begin to restructure archaeology at its core, creating a new, more equitable framework that is not supported by colonialist ideologies.

With that in mind, I also believe a transformative archaeology can learn from current discussions being held on postcolonial archaeologies, specifically when it comes to creating a transformative archaeological practice. For example, a more widespread adoption of ethnographic archaeology may provide practitioners with the tools necessary for a greater reflexivity in our archaeological research, allowing for discussion on the relations between archaeologists and community members and the ethical considerations coincide more with current social issues (Meskell 2010: 445, 453). However, even a transformative archaeology would have its pitfalls – as McDavid and McGhee (2010) warn in their commentary on postcolonial public archaeology and advocacy, we cannot fetishize our goals and make the overall aim become “practicing good archaeology” or “being a good person in archaeology” (490); ultimately, we must be doing this transformative work because it is necessary.

This Paper is an Optimistic Confrontation

Archaeology is violence. In the past and present, archaeology perpetuates both physical and socio-cultural violence in the application of its theory and practice. But there is potential for archaeology to become non-violent, to move beyond its assumed norms of “scientific destruction” and transform into a very different discipline.

Yes, this paper is confrontational, but it should not be seen as a pessimistic rant against the archaeological establishment that maintains these violent norms. On the contrary, it is through this confrontation that I hope aspiration can be born: the aspiration to become more than a discipline of and for violence, to fulfil the idea that archaeology allows us to touch the past and understand it. Much has been discussed by BIPOC academics about the concept of white imagination and how its severe limitations to see beyond whiteness help exacerbate the continued oppression and marginalisation of others (Coleman 2014; Rankine 2015; Todd 2019); I believe a similar lack of imagination is what has obstructed substantial change in archaeology. The Western (white) canon has thoroughly ingrained itself into archaeology courses for decades, developing a longstanding place in syllabi that can be easily misunderstood as “vital” or “necessary” reading, rather than just a reflection of bias and the internalised priority of whiteness. To imagine an archaeology without this foundation is nigh impossible for many, resulting in a definite pushback against those calling for radical change to the way archaeology is taught and practiced.

As an “optimistic confrontation”, I hope that this paper helps spark the imagination necessary to weaken the resistance to such change. Like I have mentioned in the introduction, this paper is meant to reflect a similar journey I’ve gone through as an archaeologist who has been confronted with the truth of my research; just as that one Internet comment shook me out of my archaeological delusions of grandeur, I hope this paper is the jolt that some require to finally recognise how much work needs to be done. We can transform our discipline into something that acknowledges our colonial baggage, but is not beholden to it. When describing decolonization, Frantz Fanon (1963) called such a massive change in the world as “a program of complete disorder” (36); similarly, the process of transformation for archaeologists will also be rife with complications and conflicts. We are looking towards necessary change and development will be hard, and dirty, and downright ugly at times…but hasn’t that always described archaeology?

References

Adriaens, A. (2005) Non-Destructive Analysis and Testing of Museum Objects: An Overview of 5 Years of Research. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy 60 (12), 1503-1516.

Allen, S. H. (1999) Finding the Walls of Troy: Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlik. Berkley: University of California Press.

Battle-Baptiste, W. (2010) An Archaeologist Finds Her Voice: A Commentary on Colonial and Postcolonial Identities. In Lydon, J. and Rizvi, U. Z. (editors) Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 387-392.

Berlin, H. (1967) The Destruction of Structure 5D-33-1st at Tikal. American Antiquity 32 (2), 241-242.

Bollogino, R., Tresset, A. and Vigne, J. (2008) Environment and Excavation: Pre-Lab Impacts on Ancient DNA Analyses. Comptes Rendus Palevol 7, 91-98.

Burke, H. and Smith, C. E. (2007) The Great Debate: Archaeology, Repatriation, and Nationalism. In Burke, H. and Smith, C. E. (editors) Archaeology to Delight and Instruct: Active Learning in the University Classroom. New York: Routledge. 55-66.

Byrne, D. (2003) The Ethos of Return: Erasure and Reinstatement of Aboriginal Visibility in the Australian Historical Landscape. Historical Archaeology 37 (1), 73-86.

Caggianni, M. C., Ciminale, M., Gallo, D., Noviello, M. and Salvemini, F. (2012) Online Non-Destructive Archaeology: the Archaeological Park of Egnazia (Southern Italy) Study Case. Journal of Archaeological Science 39 (1), 67-75.

Caple, C. (2008) Preservation In Situ: The Future for Archaeological Conservators? Studies in Conservation 53 (1), 214-217.

Carey, H. M. (2011) God’s Empire: Religion and Colonialism in the British World, c. 1801-1908. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chakrabarty, D. (1992) Postcoloniality and the Artiface of History: Who Speaks for “Indian” Pasts? Representaions 37, 1-26.

Challis, D. (2013) The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie. London: Bloomsbury.

Challis, K. and Howard, A. J. (2006) A Review of Trends Within Archaeological Remote Sensing in Alluvial Environments. Archaeological Prospection 13, 231-240.

Coleman, N. A. T. (2014) Why Isn’t My Professor Black? , http://www.dtmh.ucl.ac.uk/videos/isnt-professor-black-nathaniel-coleman/.

Corsi, C. (2013) Good Practice in Archaeological Diagnostics: An Introduction. In Corsi, C., Slapšak, B., and Vermeulen, F. (editors) Good Practice in Archaeological Diagnostics: Non-Invasive Survey of Complex Archaeological Sites. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. 1-10.

Crowther, A., Haslam, M., Oakden, N., Walde, D. and Mercader, J. (2014) Documenting Contamination in Ancient Starch Laboratories. Journal of Archaeological Science 49, 90-104.

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth. Translated Farrington, C. New York: Grove Press.

Fiskesjö, M. (2010) The Global Repatriation Debate and the New “Universal Museums”. In Lydon, J. and Rizvi, U. R. (editors) Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 303-310.

Fitzpatrick, A. (2018) Black Flags and Black Trowels: Embracing Anarchy in Interpretation and Practice. In Theoretical Archaeology Group Conference.

Fontein, J. (2010) Efficacy of “Emic” and “Etic” in Archaeology and Heritage. In Lydon, J. and Rizvi, U. R. (editors) Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 311-322.

Gaffney, C. (2008) Detecting Trends in the Prediction of the Buried Past: A Review of Geophysical Techniques in Archaeology. Archaeometry 50 (2), 313-336.

Gready, P. and Robins, S. (2014) From Transitional to Transformative Justice: A New Agenda for Practice. The International Journal of Transitional Justice 8, 339-361.

Hamilton, S. (2014) Under-Representation in Contemporary Archaeology. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 24 (1).

Hole, B. (2007) Playthings for the Foe: The Repatriation of Human Remains in New Zealand. Public Archaeology 6 (1), 5-27.

Holtorf, C. and Kristensen, T. M. (2015) Heritage Erasure: Rethinking ‘Protection’ and ‘Preservation’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (4), 313-317.

Hubert, J. and Fforde, C. (2002) Introduction: The Reburial Issue in the Twenty-First Century. In Fforde, C., Hubert, J., and Turnbull, P. (editors) The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. New York: Routledge. 1-16.

Jackson, J. M. (2018) Why Citing Black Women is Necessary. www.citeblackwomencollective.org/our-blog/why-citing-black-women-is-necessary-jenn-m-jackson.

Jenkins, T. (2016) Keeping Their Marbles: How The Treasures of the Past End Up in Museums – and Why They Should Stay There. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Langer, C. (2017) The Informal Colonialism of Egyptology: from the French Expedition to the Security State. In Woons, M. and Weier, S. (editors) Critical Epistemologies of Global Politics. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing. 182-202.

Matero, F. (2006) Making Archaeological Sites: Conservation as Interpretation of an Excavated Past. In Agnew, N. and Bridgland, J. (editors) Of the Past, for the Future: Integrating Archaeology and Conservation. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. 55-63.

Mays, S., Edlers, J., Humphrey, L., White, W. and Marshall, P. (2013) Science and the Dead: A Guideline for the Destructive Sampling of Archaeological Human Remains for Scientific Analysis. Historic England.

McDavid, C. and McGhee, F. (2010) Cultural Resources Management, Public Archaeology and Advocacy. In Lydon, J. and Rizvi, U. Z. (editors) Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 481-494.

Mertens, D. M. (2007) Transformative Paradigm: Mixed Methods and Social Justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1 (212), 212-225.

Meskell, L. (2010) Ethnographic Interventions. In Lydon, J. and Rizvi, U. Z. (editors) Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 445-458.

Nagy, R. (2008) Transitional Justice as Global Project: Critical Reflections. Third World Quarterly 29 (2), 275-289.

Nash, S. E. and Colwell-Chanthapohn, C. (2010) NAGPRA After Two Decades. Museum Anthropology 33 (2), 99-104.

Nicholas, G. and Hollowell, J. (2007) Ethical Challenges to a Postcolonial Archaeology: the Legacy of Scientific Colonialism. In Hamilakis, Y. and Duke, P. (editors) Archaeology and Capitalism: From Ethics to Politics. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. 59-82.

Rankine, C. (2015) Citizen: An American Lyric. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press.

Reid, D. M. (2002) Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. Berkley: University of California Press.

Riding In, J. (1992) Without Ethics and Morality: A Historical Overview of Imperial Archaeology and American Idians. Arizona State Law Journal 11, 11-34.

Riggs, C. (2013) Colonial Visions: Egyptian Antiquities and Contested Histories in the Cairo Museum. Museum Worlds: Advances in Research 1, 65-84.

Schanche, A. (2002) Saami Skulls, Anthropological Race Research, and the Repatriation Question in Norway. In Fforde, C., Hubert, J., and Turnbull, P. (editors) The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. New York: Routledge. 47-58.

Shigwedha, V. A. (2016) The Return of Herero and Nama Bones from Germany: the Victims’ Struggle for Recognition and Recurring Genocide Memories in Namibia. In Dreyfus, J. and Ansett, E. (editors) Human Remains in Society: Curation and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Genocide and Mass-Violence. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 197-219.

Thomas, N. (2016) We Need Ethnographic Museums Today – Whatever You Think of Their History.

Thornton, R. (2002) Repatriation as Healing the Wounds of the Trauma: Cases of Native Americans in the United States of America. In Fforde, C., Hubert, J., and Turnbull, P. (editors) The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. New York: Routledge. 17-24.

Thornton, R. (2016) Who Owns the Past? The Repatriation of Native American Remains and Cultural Objects. In Lobo, S., Talbout, S., and Morris, T. L. (editors) Native American Voices: A Reader. 3rd edition. New York: Routledge. 311-320.

Todd, Z. (2019) Your Failure of Imagination is Not My Problem. https://anthrodendum.org/2019/01/10/your-failure-of-imagination-is-not-my-problem/.

Torrej ón, J., Wallner, M., Trinks, I., Kucera, M., Luznik, N., Locker, K. and Neubauer, W. (2016) Big Data in Landscape Archaeological Prospection. Arqueol ó gica 2.0, 238-246.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd edition. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Turnbull, P. (2002) Indigenous Australians, Their Defence of the Dead and Native Title. In Fforde, C., Hubert, J., and Turnbull, P. (editors) The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. New York: Routledge. 63-86.

Uda, M., Demortier, G. and Nakai, I. (2005) X-Rays for Archaeology. The Nederlands: Springer.

Utt, J. (2013) Intent vs. Impact: Why Your Intentions Don’t Really Matter. https://everydayfeminism.com/2013/07/intentions-dont-really-matter/www.onlyblackgirl.com/blog/intent-vs-impact.

Wallis Budge, E. A. (1989) The Rosetta Stone. Reprint edition. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

If you’re financially stable enough, why not donate to help out marginalised archaeologists in need via the Black Trowel Collective Microgrants? You can subscribe to their Patreon to become a monthly donor, or do a one-time donation via PayPal.

My work and independent research is supported almost entirely by the generosity of readers – if you’re interested in contributing a tiny bit, you can donate here.